Click here for the complete list of My Weeks with The Jim Henson Hour reviews!

In his career as a filmmaker, Jim Henson directed a wide variety of projects, including feature films, TV specials, individual episodes, segments for Sesame Street, and short films like Time Piece.

In his career as a filmmaker, Jim Henson directed a wide variety of projects, including feature films, TV specials, individual episodes, segments for Sesame Street, and short films like Time Piece.

Time Piece, of course, was his first real directorial effort – a surreal, nearly wordless 8 ½-minute meditation on the passage of time and how it affects a non-descript protagonist. It’s full of weird sight gags and remarkable editing tricks. It stands as one of Jim’s most impressive achievements, and I’ve often wondered what his career would have looked like if he’d continued down that experimental path.

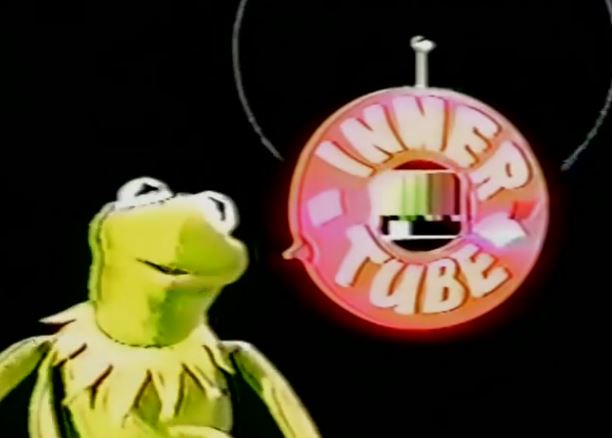

The pilot for Inner Tube (a Jim Henson Hour precursor from 1987) sees Jim returning to similar territory, and the results aren’t nearly as impressive.

It’s unfair to compare a 10-minute TV pilot to a fully-fledged short film. I understand. Jim was never going to give Inner Tube the same kind of care and attention he gave to Time Piece. But on paper, Inner Tube has the same kind of thematic coherence that the older short did. Instead of time, though, it’s about TV screens and how they dominate our lives.

This theme is announced right up front, with the opening song declaring “Everybody watching everywhere/everybody – you’re on the air!” Everything that follows supports that statement. TV and technology are the only things that matter, and no one thinks about anything else. While this might be thematic unity in theory, in practice it’s actually just kind of muddled and repetitive.

There are some good ideas here, but they seem completely inappropriate for the kind of light variety show that Inner Tube presumably would have been. The show is set in a future with 15,000 channels. Citizens are encouraged to watch TV at all times, because “you can always find a program to match your mood, your IQ, your income bracket, and your clothes.”

There are some good ideas here, but they seem completely inappropriate for the kind of light variety show that Inner Tube presumably would have been. The show is set in a future with 15,000 channels. Citizens are encouraged to watch TV at all times, because “you can always find a program to match your mood, your IQ, your income bracket, and your clothes.”

Strikingly, those words are delivered by our old friend Kermit the Frog. He also reminds us to “Remember, with InnerTube, if you’re not plugged in, you can’t get turned on.” It has the effect of making Kermit seem like he’s been turned into the friendly face of an evil overlord – the calming, reassuring presence that discourages asking questions or thinking too hard. I doubt that’s what Jim or writer David Misch intended, but that’s how it comes across.

It is absolutely terrifying.

That use of Kermit gives everything a creepy veneer. When handyman Henry chides his partner Jake for memorizing Kermit’s speech, it plays like he’s trying to break him out of a trance. When an elderly couple shrug at a man jumping out of their TV, it plays like they’ve become too desensitized to feel. There’s nothing in these moments themselves to imply that this is the case, but the world just seems like an unpleasant place to live.

Adding to that feeling is the sense that things are constantly going wrong. This is only a ten-minute show, but it has three separate characters that jump from channel to channel: the animated Glitch, the Muppet/Human hybrid Crasher, and the disembodied head Zaloom (played by comedian Paul Zaloom, later the star of Beakman’s World).

Jake and Henry’s job is to make sure everything is running smoothly with the system. I understand that. But I’d care about them a lot more if they dealt with one threat in this story. Instead there are three threats, and they don’t actually deal with any of them. They just kind of throw their arms up and grunt in frustration and then run around. This does not make them seem like ideal leads for a TV show, or like people who are good at their jobs.

Least pleasant of all is the show’s house band, which doesn’t get a name but which is completely off-putting. In their big scene, the lead singer assures Henry and Jake that technology is their friend, saying “Look at us, we do just fine and we’re surrounded by technology.” Then they repeat the word “technology” a few more times and list the various forms of technology that surround them. It’s so self-consciously “hip” and “now” that it’s hilarious.

Least pleasant of all is the show’s house band, which doesn’t get a name but which is completely off-putting. In their big scene, the lead singer assures Henry and Jake that technology is their friend, saying “Look at us, we do just fine and we’re surrounded by technology.” Then they repeat the word “technology” a few more times and list the various forms of technology that surround them. It’s so self-consciously “hip” and “now” that it’s hilarious.

Their designs are even worse. They have the same plastic Uncanny Valley look that Henson used in a few other productions around this time (such as Ghost of Faffner Hall), and they are the stuff nightmares are made of. That’s even true of Digit, who would go on to become a lovable character on JHH proper. Here he has a much more metallic voice, and it’s no fun to listen to.

In their defense, I will say that their two song numbers (by Mark Radice and a team of co-writers) are both insanely catchy. After I first got “Inner Tube” in a tape trade in high school, my younger brother and I used to sing “See See What You Can Do” all the time, and it’s been stuck in my head ever since. “Trapped” hasn’t been trapped there as often, but it’s a lot of fun too. If the purpose of the band is to keep me glued to my 15,000-channel TV, they’re a success. I’ll only turn off the TV to go buy their cassette.

On the whole though, it’s easy to see why Inner Tube didn’t get picked up as a series. In addition to all of the awkwardness and unpleasantries I already mentioned, it must have seemed derivative at the time. This particular dystopia is very similar to that of Max Headroom, the cult show that was just beginning its short run on ABC. Not only was Inner Tube poorly executed, it wasn’t even a fresh idea.

That said, a few elements of it did survive into the Jim Henson Hour as it eventually aired, most notably Digit and the idea of flipping channels. Before JHH would reach the air, though, it had to go through one more failed format. Come back next time, when Ryan will tell you all about it.

Click here to see see what you can do on the Tough Pigs Forum.

by Anthony Strand