Waaayyy back in 2009, the folks at McFarland Publishing released the sort of book we’d been hoping someone would put together: “Kermit Culture“, a series of academic essays all about the Muppets. Because we think about nerdy things like the impact of Shakespeare on The Muppet Show, or analyzing the Muppets’ roles as actors in their own films all the time. One thing was painfully apparent after reading “Kermit Culture”: There is a lot more ground to cover.

Waaayyy back in 2009, the folks at McFarland Publishing released the sort of book we’d been hoping someone would put together: “Kermit Culture“, a series of academic essays all about the Muppets. Because we think about nerdy things like the impact of Shakespeare on The Muppet Show, or analyzing the Muppets’ roles as actors in their own films all the time. One thing was painfully apparent after reading “Kermit Culture”: There is a lot more ground to cover.

So it was a pleasant non-surprise to see that “Kermit Culture” garnered a sequel. But rather than make another book about Kermit and Fozzie and Lew Zealand, “The Wider Worlds of Jim Henson” looks beyond The Muppet Show and into Fraggle Rock, The Dark Crystal, Labyrinth, The Jim Henson Hour, and more.

The Fraggle Rock section was the most fun to read, as there’s a much bigger library to pull from with the show than one of the movies or the short-lived Jim Henson Hour. Plus, there’s something hilarious about over-analyzing something as fun and goofy as the Fraggles.

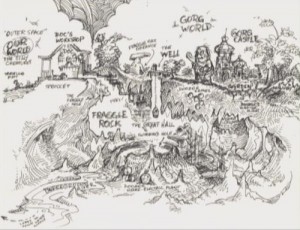

Aaron Calbreath-Frasieur’s essay, “Fraggle Rock and the Art of World Building” is a great place to start, since it’s all about the larger world of the Fraggles, Gorgs, and Doozers. It reminds us that the first episode of the series was all about Traveling Matt’s journey into Outer Space and Gobo’s newfound role as the Rock’s resident explorer. Then, over the course of the show, Fraggle Rock itself becomes larger and more realized as we find more and more locations in their underground caverns and beyond. It’s such a great metaphor for the show as a whole, which becomes more three-dimensional and vast as time goes on. It’s one of the reasons why Fraggle Rock is so fondly remembered today as such a fully-formed world and not just a puppet show in a cave.

Aaron Calbreath-Frasieur’s essay, “Fraggle Rock and the Art of World Building” is a great place to start, since it’s all about the larger world of the Fraggles, Gorgs, and Doozers. It reminds us that the first episode of the series was all about Traveling Matt’s journey into Outer Space and Gobo’s newfound role as the Rock’s resident explorer. Then, over the course of the show, Fraggle Rock itself becomes larger and more realized as we find more and more locations in their underground caverns and beyond. It’s such a great metaphor for the show as a whole, which becomes more three-dimensional and vast as time goes on. It’s one of the reasons why Fraggle Rock is so fondly remembered today as such a fully-formed world and not just a puppet show in a cave.

Next is Andrew Leal’s “Outer Spaces”. Andrew is the first of three friends-of-ToughPigs who contributed to this book, which is a real treat for us. I mean, how often do we get to see the names of our friends in official Muppet products? Andrew’s essay looks deeper into the international connections of Fraggle Rock, stemming from Jim Henson’s original pitch of a show to “bring peace to the world”, and continuing through the co-productions of the show in the UK, France, and elsewhere. It’s a great mix of a Fraggle history lesson with the added bonus of a deeper analysis of the themes that promote Jim’s dream of the program to create world peace. And it introduces another dream: One where everyone in the world actually watched the show and took Jim’s message to heart, bringing about real changes between borders. Wouldn’t that have been nice?

Next is Andrew Leal’s “Outer Spaces”. Andrew is the first of three friends-of-ToughPigs who contributed to this book, which is a real treat for us. I mean, how often do we get to see the names of our friends in official Muppet products? Andrew’s essay looks deeper into the international connections of Fraggle Rock, stemming from Jim Henson’s original pitch of a show to “bring peace to the world”, and continuing through the co-productions of the show in the UK, France, and elsewhere. It’s a great mix of a Fraggle history lesson with the added bonus of a deeper analysis of the themes that promote Jim’s dream of the program to create world peace. And it introduces another dream: One where everyone in the world actually watched the show and took Jim’s message to heart, bringing about real changes between borders. Wouldn’t that have been nice?

“No Sex, Please. We’re Fraggles!”, written by Tami Meredith and Maryanne L. Fisher, might be my least favorite essay in the book. It raises the question of whether or not Fraggles have gender roles, which is not a bad thesis. When you think about it, Red is a sporty female, Boober is a laundry-loving male, and there aren’t any gender-specific traits that either the male Fraggles or female Fraggles seem to share. But this essay tries too hard to prove that point, going into the minutae of what makes each character and trying to pin a gender role into each characteristic. The end result is boring and debatable, and the argument goes on for almost 20 pages. This sort of essay is why academic writings tend to be looked over, as it’s just another theory that sounds smart, but shouldn’t necessarily be agreed with just because it was published.

“No Sex, Please. We’re Fraggles!”, written by Tami Meredith and Maryanne L. Fisher, might be my least favorite essay in the book. It raises the question of whether or not Fraggles have gender roles, which is not a bad thesis. When you think about it, Red is a sporty female, Boober is a laundry-loving male, and there aren’t any gender-specific traits that either the male Fraggles or female Fraggles seem to share. But this essay tries too hard to prove that point, going into the minutae of what makes each character and trying to pin a gender role into each characteristic. The end result is boring and debatable, and the argument goes on for almost 20 pages. This sort of essay is why academic writings tend to be looked over, as it’s just another theory that sounds smart, but shouldn’t necessarily be agreed with just because it was published.

Where the last essay went wrong, Justin Werfel’s “The Ecology of Fraggle Rock” went right. In my overall favorite essay in the book, Werfel discusses the different species found in Fraggle Rock, from the Ditzies to the Poison Cacklers to the Toe-Ticklers , and how they all coexist in the same environment. But the brilliance of this essay isn’t just the analysis of the plants and animals in Fraggle Rock, but in the way it’s presented. Werfel uses just enough tongue-in-cheek language to make what might be a boring academic article actually funny. He presents his findings as if they were the result of a scientific study, one that lasted from 1983-1987, which explains why we only know about the species we’ve seen on the show, and not as much about the ones we’ve only heard the names of and never spotted. The best part is near the end when Werfel states, “No observations have occurred since 1987, and a tentative new expedition that would allow for renewed study, first announced in 2005, has repeatedly encountered delays and obstacles.” Think about that, folks.

Where the last essay went wrong, Justin Werfel’s “The Ecology of Fraggle Rock” went right. In my overall favorite essay in the book, Werfel discusses the different species found in Fraggle Rock, from the Ditzies to the Poison Cacklers to the Toe-Ticklers , and how they all coexist in the same environment. But the brilliance of this essay isn’t just the analysis of the plants and animals in Fraggle Rock, but in the way it’s presented. Werfel uses just enough tongue-in-cheek language to make what might be a boring academic article actually funny. He presents his findings as if they were the result of a scientific study, one that lasted from 1983-1987, which explains why we only know about the species we’ve seen on the show, and not as much about the ones we’ve only heard the names of and never spotted. The best part is near the end when Werfel states, “No observations have occurred since 1987, and a tentative new expedition that would allow for renewed study, first announced in 2005, has repeatedly encountered delays and obstacles.” Think about that, folks.

Part two of the book, which ventures into the world of Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal begins with Gideon Haberkorn’s “Interpreting the Various Species in The Dark Crystal and Fraggle Rock“. It’s a good segue from the Fraggle section into the fantasy films, but there isn’t much to learn that you can’t get from the title. Both worlds include a slew of different species (and, as I count them, only one human between the two), all of which play an important role, fulfill an archetype, and help to fill the world and make it feel more real. That’s not to say this article is dull, because it’s not, but it is guilty of being more informative than innovative, which we might need to legitimize an academic anthology like this one.

Part two of the book, which ventures into the world of Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal begins with Gideon Haberkorn’s “Interpreting the Various Species in The Dark Crystal and Fraggle Rock“. It’s a good segue from the Fraggle section into the fantasy films, but there isn’t much to learn that you can’t get from the title. Both worlds include a slew of different species (and, as I count them, only one human between the two), all of which play an important role, fulfill an archetype, and help to fill the world and make it feel more real. That’s not to say this article is dull, because it’s not, but it is guilty of being more informative than innovative, which we might need to legitimize an academic anthology like this one.

I am generally not a huge Dark Crystal fan. I love the art and puppetry in the film, and I think that every frame is stunning, but the story tends to drag on in my opinion. “Union, Nature, and Aughra in The Dark Crystal” by Roxanne Harde and “A Natural History of The Dark Crystal: The Conceptual Design of Brian Froud” by Catriona McAra actually made me want to put down my book and put in my old VHS of the movie to follow along with their theses. Harde discusses the split nature of the Skeksis and Mystics, and how it relates to the Gelflings, the Podlings, and especially Aughra, reminding me that the nature of duality is prevalent throughout the entire film, and that the mythology runs a lot deeper than I recalled. Meanwhile, McAra’s essay delved deeper into the art of the film, which is so much more epic and fully realized than anyone would’ve expected (though I guess not, if you know anything about Jim Henson and Brian Froud). The next time I watch The Dark Crystal, I’ll definitely be thinking of both of these articles.

I am generally not a huge Dark Crystal fan. I love the art and puppetry in the film, and I think that every frame is stunning, but the story tends to drag on in my opinion. “Union, Nature, and Aughra in The Dark Crystal” by Roxanne Harde and “A Natural History of The Dark Crystal: The Conceptual Design of Brian Froud” by Catriona McAra actually made me want to put down my book and put in my old VHS of the movie to follow along with their theses. Harde discusses the split nature of the Skeksis and Mystics, and how it relates to the Gelflings, the Podlings, and especially Aughra, reminding me that the nature of duality is prevalent throughout the entire film, and that the mythology runs a lot deeper than I recalled. Meanwhile, McAra’s essay delved deeper into the art of the film, which is so much more epic and fully realized than anyone would’ve expected (though I guess not, if you know anything about Jim Henson and Brian Froud). The next time I watch The Dark Crystal, I’ll definitely be thinking of both of these articles.

ToughPigs’ own Tom Holste contributed “Finding Your Way Through Labyrinth“, explaining why the movie is great and everyone who disagrees can suck it. Okay, that’s not exactly what he said, but my own love of Labyrinth came through in my enthusiasm. Tom refutes the early complaints about Labyrinth with explanations as to why their points are invalid (i.e. Jim’s history with “sick humor” justifying the silly amputations of the Fireys), and then goes on to reference the rest of Jim Henson’s history of work with comparisons to other productions with the themes of time, being trapped, projections of sexuality, and more. Tom’s essay made me excited about Labyrinth all over again (not that I needed much encouragement), and he reminded me about how well the film fits in with Jim’s entire oeuvre.

ToughPigs’ own Tom Holste contributed “Finding Your Way Through Labyrinth“, explaining why the movie is great and everyone who disagrees can suck it. Okay, that’s not exactly what he said, but my own love of Labyrinth came through in my enthusiasm. Tom refutes the early complaints about Labyrinth with explanations as to why their points are invalid (i.e. Jim’s history with “sick humor” justifying the silly amputations of the Fireys), and then goes on to reference the rest of Jim Henson’s history of work with comparisons to other productions with the themes of time, being trapped, projections of sexuality, and more. Tom’s essay made me excited about Labyrinth all over again (not that I needed much encouragement), and he reminded me about how well the film fits in with Jim’s entire oeuvre.

Closing out the fantasy films section of the book is David R. Burns and Deborah Burns’ “Anti-Consumerism in Labyrinth“. The Burnses take the film scene-by-scene, with a big focus on the one in the junkyard, and explore the role consumerism took in Sarah’s downfall, and then how the fact that she was able to let go of her “things” to rehabilitate herself. It’s a good lesson that sometimes gets lost among the faeries and talking dogs and Bowie crotches in the movie, one that Jim supposedly felt strongly about, so it’s nice to have it laid out in black-and-white in this essay.

Closing out the fantasy films section of the book is David R. Burns and Deborah Burns’ “Anti-Consumerism in Labyrinth“. The Burnses take the film scene-by-scene, with a big focus on the one in the junkyard, and explore the role consumerism took in Sarah’s downfall, and then how the fact that she was able to let go of her “things” to rehabilitate herself. It’s a good lesson that sometimes gets lost among the faeries and talking dogs and Bowie crotches in the movie, one that Jim supposedly felt strongly about, so it’s nice to have it laid out in black-and-white in this essay.

Part three is entitled “Storytellers and Specials”, and it begins with our third and final ToughPigs representative, ToughPigs contributor Anthony Strand. Anthony’s article, “Everyone’s a Storyteller”, investigates the way stories are told, and by whom, in both sections of The Jim Henson Hour. For example, Jim acts as the storyteller when he presents the MuppeTelevision segment, which includes Kermit as the storyteller who chooses what skeches will air, which might include a “Bootsie and Brad” segment which takes place in the imagination of a little girl, and so on. He does the same with “The Storyteller”, looking deeper into the Storyteller’s role in the story, both as a participant and an omnipresent narrator. It’s a really interesting view on the series that not many people have taken before. And now it’s making me wonder if I’m the storyteller for this review, or if it’s something else entirely…

Part three is entitled “Storytellers and Specials”, and it begins with our third and final ToughPigs representative, ToughPigs contributor Anthony Strand. Anthony’s article, “Everyone’s a Storyteller”, investigates the way stories are told, and by whom, in both sections of The Jim Henson Hour. For example, Jim acts as the storyteller when he presents the MuppeTelevision segment, which includes Kermit as the storyteller who chooses what skeches will air, which might include a “Bootsie and Brad” segment which takes place in the imagination of a little girl, and so on. He does the same with “The Storyteller”, looking deeper into the Storyteller’s role in the story, both as a participant and an omnipresent narrator. It’s a really interesting view on the series that not many people have taken before. And now it’s making me wonder if I’m the storyteller for this review, or if it’s something else entirely…

The next few essays all tackle a similar theme. Nathaniel Long’s “There Is No One Story”, Catherine Edwards’ “The Gift of the Muppets”, and Jennifer C. Garlen and Anissa M. Graham’s “Telling Toy Stories in The Christmas Toy” all compare their respective Henson productions to familiar stories in great detail. “There Is No One Story” investigates The Storyteller‘s episodes and how they correspond with the fairy tales and myths that inspired them. “The Gift of the Muppets” discusses how Emmet Otter’s Jug Band Christmas compares to “The Gift of the Magi”. “Telling Toy Stories…” take an opposite approach by comparing The Christmas Toy with Toy Story, which premiered almost a decade later. Each of these three essays then delved into in-depth descriptions of the plots and meanings behind their Henson productions, which offer little new information, but are still entertaining and well written.

The next few essays all tackle a similar theme. Nathaniel Long’s “There Is No One Story”, Catherine Edwards’ “The Gift of the Muppets”, and Jennifer C. Garlen and Anissa M. Graham’s “Telling Toy Stories in The Christmas Toy” all compare their respective Henson productions to familiar stories in great detail. “There Is No One Story” investigates The Storyteller‘s episodes and how they correspond with the fairy tales and myths that inspired them. “The Gift of the Muppets” discusses how Emmet Otter’s Jug Band Christmas compares to “The Gift of the Magi”. “Telling Toy Stories…” take an opposite approach by comparing The Christmas Toy with Toy Story, which premiered almost a decade later. Each of these three essays then delved into in-depth descriptions of the plots and meanings behind their Henson productions, which offer little new information, but are still entertaining and well written.

The fourth and final section (don’t worry folks, we’re in the home stretch) is “Journeys Forward and Back”, which seems to be the “other” category for this collection. Michael J. Berntsen starts us off with “The Muppetry of Nightmares”, in which he picks episodes of The Cosby Show (“Cliff’s Nightmare”, which features Gonzo, Sweetums, Statler, a Muppet hoagie, and more), Chappelle’s Show (the “Kneehigh Park” Sesame Street parody), and Saturday Night Live‘s “Land of Gorch” sketches to show how the Muppets’ influence spreads to other series. Some included actual Henson participation, some included adult humor, and all three use very different methods of spoofery. Jim’s influence reached far beyond his own productions, and there are some really good arguments for why these three are among the most memorable.

The fourth and final section (don’t worry folks, we’re in the home stretch) is “Journeys Forward and Back”, which seems to be the “other” category for this collection. Michael J. Berntsen starts us off with “The Muppetry of Nightmares”, in which he picks episodes of The Cosby Show (“Cliff’s Nightmare”, which features Gonzo, Sweetums, Statler, a Muppet hoagie, and more), Chappelle’s Show (the “Kneehigh Park” Sesame Street parody), and Saturday Night Live‘s “Land of Gorch” sketches to show how the Muppets’ influence spreads to other series. Some included actual Henson participation, some included adult humor, and all three use very different methods of spoofery. Jim’s influence reached far beyond his own productions, and there are some really good arguments for why these three are among the most memorable.

Jennifer Stoessner’s “Dinosaurs and the Evolution of The Jim Henson Company” and Sherry Ginn’s “Exploring the Alien Other on Farscape” both investigate post-Jim productions and how Jim’s methods of storytelling and technology continued on after his passing. (Full disclosure: I skimmed the Farscape article, as I am currently watching the series for the first time and wanted to avoid spoilers.) It’s interesting to see how The Jim Henson Company keeps Jim’s vision alive through successes like these, while staying original and innovative.

Jennifer Stoessner’s “Dinosaurs and the Evolution of The Jim Henson Company” and Sherry Ginn’s “Exploring the Alien Other on Farscape” both investigate post-Jim productions and how Jim’s methods of storytelling and technology continued on after his passing. (Full disclosure: I skimmed the Farscape article, as I am currently watching the series for the first time and wanted to avoid spoilers.) It’s interesting to see how The Jim Henson Company keeps Jim’s vision alive through successes like these, while staying original and innovative.

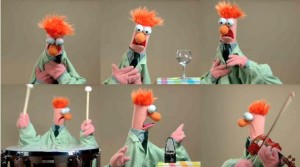

“Muppet Memes, or Beaker Conquers YouTube” by Anissa M. Graham cheats the “Wider Worlds of Jim Henson” pitch by returning to the Muppet Show family of characters by looking at their recent works on YouTube. This short essay recaps the Muppets’ official history with online videos from Muppets.com to videos like “Classical Chickens”, “Ode to Joy”, and “Habanera” to the smash hit of “Bohemian Rhapsody” to the parody trailers for The Muppets. Like a few of the other articles in this anthology, this essay is more informative than analyzing, but a little YouTubian history never hurt anyone.

“Muppet Memes, or Beaker Conquers YouTube” by Anissa M. Graham cheats the “Wider Worlds of Jim Henson” pitch by returning to the Muppet Show family of characters by looking at their recent works on YouTube. This short essay recaps the Muppets’ official history with online videos from Muppets.com to videos like “Classical Chickens”, “Ode to Joy”, and “Habanera” to the smash hit of “Bohemian Rhapsody” to the parody trailers for The Muppets. Like a few of the other articles in this anthology, this essay is more informative than analyzing, but a little YouTubian history never hurt anyone.

I have to admit, I was a little disappointed with the final essay, Jennifer C Garlen’s “Fandom and Nostalgia in Disney’s The Muppets“. Not because it was poorly written or debatable or boring, because it was none of those. I was dismayed because ToughPigs is a Muppet fan site, and we were heavily involved with all of the news surrounding the 2011 film, and the essay’s title led me to believe that we would factor into this analysis of Muppet fandom. Of course, I was dead wrong, and the article title instead refers to fandom inside the film. Things like Sweetums’ job at Mad Man Mooney’s and Sons, references to The Muppet Movie and The Muppets Take Manhattan, and pretty much everything about Walter and Gary. The amount of fan service in the film was most definitely impressive (albeit a point of contention among uberfans), and maybe we would’ve gotten a mention in this article if Jason Segel slipped a ToughPigs cameo into the film somehow. Or if Walter’s ToughPigs name-drop made it into the final film.

I have to admit, I was a little disappointed with the final essay, Jennifer C Garlen’s “Fandom and Nostalgia in Disney’s The Muppets“. Not because it was poorly written or debatable or boring, because it was none of those. I was dismayed because ToughPigs is a Muppet fan site, and we were heavily involved with all of the news surrounding the 2011 film, and the essay’s title led me to believe that we would factor into this analysis of Muppet fandom. Of course, I was dead wrong, and the article title instead refers to fandom inside the film. Things like Sweetums’ job at Mad Man Mooney’s and Sons, references to The Muppet Movie and The Muppets Take Manhattan, and pretty much everything about Walter and Gary. The amount of fan service in the film was most definitely impressive (albeit a point of contention among uberfans), and maybe we would’ve gotten a mention in this article if Jason Segel slipped a ToughPigs cameo into the film somehow. Or if Walter’s ToughPigs name-drop made it into the final film.

All in all, I had a lot of fun reading “The Wider Worlds of Jim Henson”. The academia was easier to swallow than certain parts of “Kermit Culture”, it inspired me to revisit certain productions that I haven’t seen in a long time, and I learned a lot along the way. Mostly, it forced me to think about Fraggles, Hoggles, Gelflings, and Storytellers in new ways, which is great, because I plan on rewatching those movies and TV shows over and over again, and I’m always grateful for new things to look out for.

“The Wider Worlds of Jim Henson” is available on the McFarland Publications website, or you can purchase it on Amazon.

Click here to overanalyze a Doozer on the ToughPigs forum!

by Joe Hennes – Joe@ToughPigs.com