Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Hey, quick question for ya. Is the labyrinth in Labyrinth real?

I mean, of course it’s fictional, but is it real within the movie? Has the labyrinth always been there independently of Sarah? Did Sarah dream it up? Did Jareth dream it up? See, if you ask if the labyrinth is real, that one question turns out to be a bunch of little questions in a trench coat.

Lucky for us, there’s a nifty little critical lens in literary theory that we can use to figure out exactly what kind of story this is! Hooray for nerds! This’ll be a piece of cake.

Chapter One: Yes, It’s Already Time for the Academic Part of the Article

In his 1973 text The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, Tzvetan Todorov presents a unique schema for approaching fantasy that places the “reality or dream” question at the center of the fantastic.

He lays out the way magical stories work thusly: “In a world which is indeed our world, the one we know, a world without devils, sylphides, or vampires, there occurs an event which cannot be explained by the laws of this same familiar world. The person who experiences the event must opt for one of two possible solutions: either he is the victim of an illusion of the senses, of a product of the imagination – and laws of the world then remain what they are; or else the event has indeed taken place, it is an integral part of reality – but then this reality is controlled by laws unknown to us.”

In Todorov’s nomenclature, “marvelous” is when the supernatural or magical events actually happened, while “uncanny”, a term borrowed from Freud, is when it can all be explained away as the product of the character’s psyche. While these words are rarely used this way outside of this specific structuralist schema, it can be useful for categorization. We can easily place The Wizard of Oz and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in the uncanny category, while Brigadoon is an example of the marvelous.

Todorov continues, “The fantastic occupies the duration of this uncertainty. Once we choose one answer or the other, we leave the fantastic for a neighboring genre, the uncanny or the marvelous. The fantastic is that hesitation experienced by a person who knows only the laws of nature, confronting an apparently supernatural event.”

Chapter Two: Labyrinth the Marvelous

As noted in the introduction to this article series, we do not see Sarah go to sleep at the start of her adventure or wake up at the end. The events in the labyrinth include moments that do not include her, such as the “Magic Dance” number. She is oblivious to the conversations between Jareth and Hoggle that lead to her unfortunate bite of the peach. This isn’t how a dream movie like The Wizard of Oz works, and it certainly isn’t how dreams work. Further, the characters seem to have been around for a while, such as when one of the False Alarms that Hoggle tries to shut up says, “I haven’t said it for such a long time!”

Therefore, the labyrinth is real, and Labyrinth is marvelous. Sure, maybe the labyrinth is filled with characters and images from her real life, but that’s probably just Jareth’s doing. So we’ll say the labyrinth itself is definitely real and everything in it actually happened, with the caveat that a magical Goblin King created living versions of items from her bedroom. This caveat would only include stuff like her ballgown, the cleaners, the Escher room, the Fireys, Ludo, Hoggle, Jareth, the labyrinth itself… oh shoot.

Chapter Three: Okay, Um… Labyrinth the Uncanny?

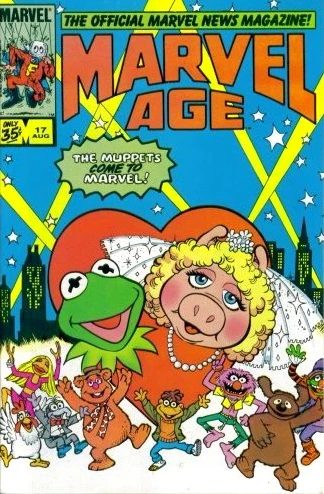

Despite what the comics would have you believe, there’s no way this fantasy world was just… around, right? It’s all so tailored to her interests. Its rules follow those in the bedtime story she tells Toby and the play she’s memorizing! Heck, even the architecture of the park in the very first shot appears in the world of the labyrinth.

It just makes sense to suppose that this is a dream of some sort, or at least that the magic takes its form from pieces of her life, and probably even subconscious desires in the case of Jareth. The narrative certainly operates on a kind of dream logic, even if that ends up alienating certain viewers, including the aforementioned disgruntled critic Roger Ebert.

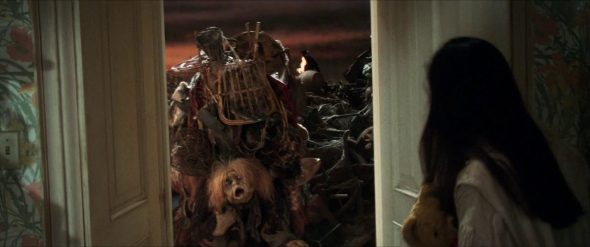

“Consider, for example, the scene in Labyrinth where Sarah thinks she is waking up from her horrible dream and opens the door of her bedroom,” Ebert writes. “Anything could be outside that door.” For him, the movie is so dreamlike that everything feels arbitrary.

This is at its most extreme at the very end, when all the fantasy characters appear in her real bedroom, even though this doesn’t follow from any established operations of the magic of this world. Of course, this part doesn’t happen in the dream world anyway, and neither does the magic wish to the goblins at the beginning, so it just goes to show you that Labyrinth never lets the viewer be settled in knowing where reality stops and dreams begin… oh shoot.

Chapter Four: Labyrinth the Fantastic, and That’s Final!

This movie is so committed to keeping us uncertain and disoriented about the form or extent of fantasy we’re seeing that it transitions into a fantasy dream sequence while already in a fantasy dream world. You know, the part where she turns into a princess at a masked ball? More remarkably, this fantasy dream sequence within a fantasy dream story is immediately followed by its inverse: a fantasy reality sequence within a fantasy dream story.

Given the magical nature of the labyrinth, a place where a perfect facsimile of Sarah’s bedroom can be found in a junkyard, they didn’t need to make the masked ball a hallucination, did they? There could have simply been a ballroom. She turns a corner and she’s wearing a gown. Done. Yet, she has to eat a trippy peach and get spaced out first, during which we hear a piece from Trevor Jones’ score entitled “Hallucination”. Remember at the beginning when Jareth said his crystal ball could show her her dreams? Well, this is the part when she goes into the ball (a galaxy-brain visual pun), so I’m inclined to think this part, even more than the rest of the story, is a dream. Perhaps a dream within a dream – a labyrinception – but it is still our uncertainty about how to interpret the magical events unfolding before us that captures our attention.

This makes sense for a movie that keeps trying to teach us not to take things for granted, which is a huge problem for Sarah from the jump. When Jareth first appears, Sarah asks, “You’re him, aren’t you? You’re the Goblin King!” See what happened there? That first sentence is a question, but she immediately follows it with a statement, and one that already decides who Jareth is supposed to be before he’s introduced himself.

When he shows her the labyrinth, she is completely unsurprised. She immediately takes it for granted that it’s all real, then suddenly decides it was all a dream in the junk sequence, and then instantly returns to her original position. She never asks this question that we’re asking, and the movie doesn’t prompt us to ask it either. By the end, with the bedroom party scene destroying any semblance of a boundary between reality and fantasy, we aren’t even able to ask the question, because there’s no distinct “labyrinth” to interrogate. There’s just Labyrinth. I guess there’s no room in this film for the hesitation and uncertainty Todorov writes about when defining the fantastic, which means… oh shoot, shoot, shoot!

Chapter Five: Labyrinth the Destroyer

Oh no! Labyrinth destroyed our analytical framework! It’s almost as though structuralism is extremely limited in its critical capacity!

Okay. It’s time for me to put my cards on the table, or at least some of them. I’m writing this article series largely because my friend Kristi has asked me repeatedly to share more of my thoughts on Labyrinth. You’ve likely encountered her work before, some of which has been featured here on ToughPigs, but you may not have known that she’s also a writer. She wrote a terrific piece on the question of the labyrinth’s reality/unreality last summer, which quotes a 3,000-word essay I sent in response to her draft of that piece, and this “My Week” series is loosely adapted from that. Now, her article argues that the labyrinth isn’t real, and I kind of agree, but complicatedly so.

This may sound like cheating, but I say the labyrinth is “real enough”. It’s perfectly common for a work of fiction to construct its whole world specifically for the personal growth of the protagonist, and Labyrinth simply takes that to the extreme – or, perhaps, to its logical conclusion. Both of its worlds are Sarah’s world, are in conversation with Sarah and her mind, and exist in conversation with each other. It’s all in concert, it’s all incongruous, and it’s all a dream – not a dream that starts when Sarah is in bed, but a dream that starts here:

The word for this kind of work is not fantasy or uncanny, but surrealist, which Mr. Google tells me means, “relating to the avant-garde movement in art and literature which sought to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind or its exponents.” Labyrinth is not a fantasy film that employs surrealist elements in the service of its fantasy so much as it is a surrealist film that employs fantasy elements in the service of its confrontation with the subconscious.

This is a productive understanding of the movie for a couple of reasons. For one, it makes the movie sound fancy-shmancy and legitimate, which I enjoy for selfish reasons as someone who’s determined to defend this movie no matter what. I don’t hear critics like Ebert complaining about Fellini. The more important point is that this actually deals with Ebert’s objection, both in the abstract and in particular. It may seem as though anything could be outside the door of Sarah’s fake junk room, but in that moment, we need whatever’s on the other side of the door to either confirm or deny Sarah’s specific conviction that she’s back home. The movie replies with precisely the answer we fear most, though part of us knows it’s coming. That’s not random.

In moments that are less straightforward, we still find scenes that seem like a detour conversing with the rest of the text, albeit not in the way we’re used to from narrative films. Consider when Jareth tells Hoggle, derisively, “I’m surprised at you, losing your head over a girl,” prompting Hoggle to insist he hasn’t. In the very next scene, a Firey says, “Like the man said, don’t lose your head!” Sarah proceeds to defeat the Fireys by making them lose their heads. The movie operates as though all of its facets share one subconscious. This even extends to the “real” world, where Sarah’s stepmother is the first one to suggest that Sarah sees her as “a wicked stepmother in a fairy story” before Sarah soon fleshes out the rest of that story.

With this film, Jim went back to his roots as an avant-garde filmmaker, only now with the runtime to do more than a quick montage experiment like Time Piece. Here, we see a character step into the subconscious world that is always part of our real world and come out of it with insight. Her frightening findings are often as uncomfortable for us to confront as they are for her, but perhaps they can also be as enlightening. Once we stop calling Labyrinth a fantasy film and start calling it a surrealist film, maybe – just maybe – understanding Labyrinth really will be a piece of cake.

Click here to insist that Jim Henson would have loved this piece of cake on the ToughPigs Discord!

by J.D. Hansel – jdhansel@toughpigs.com