Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4

Welcome to part 2 of our interview with Bonnie Erickson, former head of the Muppet Workshop and current Executive Director of the Jim Henson Legacy. Click here for part 1! In this second installment, Ms. Erickson discusses some of the more challenging Muppets to design and build, her fondness for Statler and Waldorf, and the origin of Miss Piggy!

TP: Can you think of some of the more challenging puppets that you ever had to build for The Muppet Show?

TP: Can you think of some of the more challenging puppets that you ever had to build for The Muppet Show?

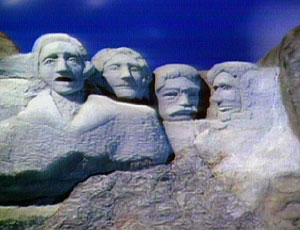

BE: Well, not challenging so much, but Mount Rushmore. It was this huge wall of foam.

TP: How big was that puppet?

BE: That whole wall was probably eight feet by six or seven feet tall. It’s huge! I think we still have it. I know we have the heads, that were separate, of the different presidents.

Because of my archiving of all these materials that the family has in their collection, I now have a very good idea of the life span of these materials. Scott foam turns to dust. Doesn’t take too long. But the soft foam, oddly enough, if it’s protected, with the glues or with the flocking, or even with latex paint, anything like that that protects it, and it’s kept out of the light and air, it lasts for quite a while. Some of those very early puppets are a little dry, but they’re still extant. Whereas the Scott foam or the insulation foam returns to what it was, only sticky. Just tiny little globules of plastic.

On Mount Rushmore, there was a woman named Janet Lerman who came in to assist with some of the projects, and one of the jobs I gave her was to carve the different presidents’ heads. She worked with John Lovelady and a couple people in the shop, but John was pretty much in charge of that building of the mountain. That was a bit of a challenge because the size was difficult, and then fitting the pieces together, being able to make it movable, stand up, have puppeteers behind it, and able to have access to it. But it was very successful, and it was one of my favorite pieces.

Another challenge was when we were on 67th Street in a small, one-floor studio area, and we built Sam the Robot for Sesame Street. I can’t believe Faz Fazakas allowed us to do this, because he was usually the one who would make sure we didn’t make these mistakes, but we built it… and then we had to take it apart again to get it out the door and down the stairs! That was also a challenge, because we were trying to use found objects, and that was a build that took some time. I think it lasted a few seasons on Sesame Street, but really, the other pieces that were more anthropomorphic and easily done were more successful.

Another challenge was when we were on 67th Street in a small, one-floor studio area, and we built Sam the Robot for Sesame Street. I can’t believe Faz Fazakas allowed us to do this, because he was usually the one who would make sure we didn’t make these mistakes, but we built it… and then we had to take it apart again to get it out the door and down the stairs! That was also a challenge, because we were trying to use found objects, and that was a build that took some time. I think it lasted a few seasons on Sesame Street, but really, the other pieces that were more anthropomorphic and easily done were more successful.

TP: And for Sam – the puppeteer was actually inside?

BE: Inside, yes.

TP: Looks like it would be cramped.

BE: Yes, it would be! (Laughs) Everybody’s used to that! I didn’t puppeteer often, because it was not something that I really wanted to do, but there were times when everybody had to get together and do a hand. I remember being packed into the cupboard with ten other puppeteers and going, “They really like this?!” (Laughs) And of course, they did!

TP: Did you have any favorite characters to design?

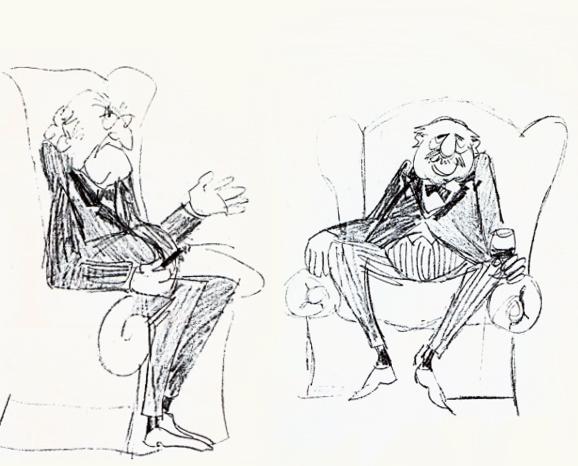

BE: I loved Statler and Waldorf. Partly I love them because I loved doing the bodies. I loved the curvature, I loved all of that part of it. I have some photos of them “naked,” just the foam—

TP: That’s a little disturbing.

BE: Yeah, it is! I kept wanting to show them in a steam bath. I thought that would be really, really funny.

TP: And appropriate for the characters, I think. I could see that.

BE: Yes. But the under-bodies, we never treated them as we did the faces. I loved the engineering, if I do say so myself. I was very pleased with the shapes that came out, because they were very different.

I thought they were funny guys… I guess part of it is because I thought of them going past the Yale Club. Every time I would work late, which was often when we were preparing for Muppet Show stuff, or any of those projects, I would go home at night in a cab if it was really late – thank you, Jim – and we’d go past the Yale Club, and I would look in there, and I would picture these guys sitting there, with their brandy, and their cigars, and the big portraits hanging on the wall. I just did a rough sketch and gave it to Jim, and I think it was almost a year later when Jim said, “I think we should do these now.” They were starting to look for ideas for Sex and Violence and all these pilots that they were trying to do.

TP: So your design actually came before the script.

TP: So your design actually came before the script.

BE: Absolutely. A long time before. Often when some of us were building these things, there were no sketches. We went right to the material. Miss Piggy – there were three pigs that I did, and they came right from the foam. Maybe some very rough ideas of what the profile should be, but they weren’t ever drawn until they existed. So people came to designs in different ways.

I loved caricatures, so the two old men and the Country Trio were really great fun. I designed [the Country Trio]; I built Frank Oz and Jim, and Don Sahlin did Jerry Nelson, and it was just such a kick to see the guys wearing their puppets and doing this thing. I have a picture, just a snapshot of Jim going (smiles) with his mouth open and the puppet’s mouth open. I don’t think anybody really knew exactly where they’d use them. There were just times when we were able to experiment a little bit.

TP: So you were able to go through all the nuts and bolts of building a puppet without having a production attached to it?

TP: So you were able to go through all the nuts and bolts of building a puppet without having a production attached to it?

BE: Sometimes. When we started out playing around with carving foam, I think the first thing we did, Jim and I worked on a thing for The Ed Sullivan Show called the Glutton. We built it out of patterned foam, but we started carving things like noses, and the little one was carved of a solid piece. We started playing around with that and seeing the possibilities. The next thing we were actually able to use that process on was, again, a combination of flat patterns and carving, and that was The Musicians of Bremen. I did all those humanoid figures. The cartoon and caricature nature of it was what I really liked. I started realizing that those caricature pieces were what I really had some interest in, and some skill with. Then we started expanding and other people started doing that too, but the process could be really frustrating.

Here’s a challenge: Statler. I had him almost done, and it means that you carve a block of foam, you scissor it until you have it the shape you want, you’ve added separate pieces for the nose, the ears, you’ve done them all separately, you start gluing them together, you’ve already made the hole inside for the puppeteer to be able to get in and move it, and you try to make it so when one finger moves, a certain part of the anatomy of that face will move, so that it’s predictable in what they can do with it… Once you have that all done, and before it’s all finished, you sand it. And you sand it on a big belt sander, but you have to hang on to it, because the minute you lose your concentration, it will grab that piece of foam.

I went up to the sander, and I had just this one little spot that I wanted to finish on Statler… and I lost my concentration for just a second, and it took the head and went right through the sander, and ended up in the room on the other side, with a hole right through the middle of this complicated puppet… It was very frustrating, and I had to start all over again.

The fact that we could make these things as smooth as we did without casting them was really interesting, and time-consuming, but it really made a difference in how everything looked. And of course Jim was always interested in “how it lit.” How it looked on television, how the camera would see it. That’s why he loved the Scott foam, because it dyed beautifully, it picked up the light, the pores somehow grabbed that light and just made it lively. The same thing happened with things that were flocked, so his eye for the lighting and the camera angles and what he would do was also part of it. Every time I think of the things that he had in mind as he was doing the designs, I’m just more and more impressed. And that he could be a nice guy as well, was pretty amazing. It was fun to work for him, and it made everybody feel good because the stuff was looking good.

I remember being very, very frightened of spending some money on some elegant fabric for the king for something we were doing – I think it might have been Frog Prince. I had forgotten to tell him how much it was, and I was just sweating bullets. I thought, Oh my God, I’ve got to tell him, and he just said, “Okay, whatever you need,” and I went, “Oh, right!”

That doesn’t mean he was profligate with money, but he appreciated the fact that people felt they needed to do certain things a certain way, and you could always make the argument. He would say no if he felt it really wasn’t necessary, but I think his opinion was, the more detail you put into something, people may not realize that it’s there, but it builds on the whole perception. Also, if you’re going to see things again and again, you’re going to find things that you didn’t see the first time. But the details were very important to him too, and certainly when you see Dark Crystal and see the things that were done that nobody’s going to see the first time around, it’s amazing.

TP: Do you think Jim had an idea, before the days when you could videotape something or buy a movie on the stand, that people would be watching these over and over again?

BE: I think he did. At a certain point in time we started saving things. I remember when we found the Bert and Ernie on the napkin. And when I left, I had in my portfolio the Statler and Waldorf sketches, and Al Gottesman, who was the Henson attorney at the time, called and said, “Would you mind giving those back for the archives?” and I said no problem. They started to build up this wonderful archive of information, drawings, sketches, scripts. Jim knew that there was a future for all of this. Whether he knew specifically how that would all play out, I’m not sure, but he was a very positive thinker, and I think he knew there was an afterlife for all of this stuff, one way or another.

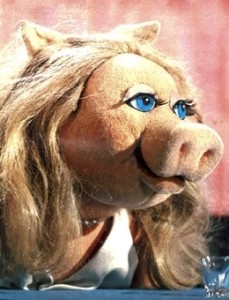

TP: We touched on some of these characters you designed… I want to go back and ask a few specifics about them, starting with Miss Piggy. Did you have an idea in those early days that she was going to be as big as she became?

TP: We touched on some of these characters you designed… I want to go back and ask a few specifics about them, starting with Miss Piggy. Did you have an idea in those early days that she was going to be as big as she became?

BE: Well, I’ve often said she and I knew, but nobody else did. (Laughs)

But I would say no… Jim came and asked me to do three pigs, because he and Jerry Juhl had written a piece called Return to the Planet of the Pigs. For that particular one, he wanted three pigs, so I did a female pig and two male pigs. One ended up being Dr. Strangepork. One, I don’t think he ever had a name, but he’s just a background pig. And the other was this female pig.

My mother had grown up in Drayton, North Dakota, and she was a big fan of Peggy Lee. At the time, Peggy Lee was always referred to as “Miss Peggy Lee,” a wonderful jazz singer, who was also getting on in years, although she was still performing. I started to think in terms of this pig being a “Piggy Lee,” so for a long time I called her “Miss Piggy Lee.” Eventually we were encouraged to change it to “Miss Piggy” because we didn’t want to offend Peggy Lee, but on the other hand, I really made that naming as an homage to her, and as it turns out, Peggy Lee also had a very strong-willed mind of her own, and so does Miss Piggy.

She existed as a pig, but she didn’t have the big eyes and all of that, initially. You can look at some of the sketches from Sex and Violence and see she had little button eyes, and she was very cute and perky and all that. But then we were doing The Herb Alpert Show, and they wanted to do this bit that had a sexy female pig with this big, gruff agent. Again, it was a time constraint. So we had some lavender satin, which we threw into a dress. I had to take the arms off that I had made for her, because she had hooves originally. I didn’t have time to actually carve fingers or anything, so I wired this purple glove. I put pearls around her neck because I wanted to hide that seam from her neck to her body, all of which ended up being part of her signature for many years to come. And she got the big eyes — I went to the drawer, I got the big eyes, I got the lashes, and over time you can see her evolution as she became more and more beautiful, and less and less the little pig from the background.

She existed as a pig, but she didn’t have the big eyes and all of that, initially. You can look at some of the sketches from Sex and Violence and see she had little button eyes, and she was very cute and perky and all that. But then we were doing The Herb Alpert Show, and they wanted to do this bit that had a sexy female pig with this big, gruff agent. Again, it was a time constraint. So we had some lavender satin, which we threw into a dress. I had to take the arms off that I had made for her, because she had hooves originally. I didn’t have time to actually carve fingers or anything, so I wired this purple glove. I put pearls around her neck because I wanted to hide that seam from her neck to her body, all of which ended up being part of her signature for many years to come. And she got the big eyes — I went to the drawer, I got the big eyes, I got the lashes, and over time you can see her evolution as she became more and more beautiful, and less and less the little pig from the background.

I love the story of it, because if you look at the first season of The Muppet Show, you’ll see she’s in the chorus line, and then she starts getting slightly bigger parts, but it was when finally Frank did that thing with the karate chop that really became the personification of Miss Piggy. Frank’s investment of the personality for Miss Piggy is what really made her famous. She and I had no idea when we were first working together that that was going to happen. (Laughs.) But I’m delighted it has, and certainly again the combination of Jim and Frank — that very special magic, and the comedy team that they were together was phenomenal. Made it all work.

TP: Were you the one who carved the later Miss Piggys after that first one?

BE: No, I think after I left she was re-carved again in the same way. I think Mari Kaestle might have been the person who did that, but I’m not sure. Eventually they found a way to make it out of foam, which is what they have been doing up ’til now. I don’t know if that’s something they’re going to continue to do, but doing it that way is more fragile. The pig as I did her, I could probably still put my hand in and move her mouth and all that, but even that was delicate. Any sharp corners were vulnerable, so I would try to make them rounded wherever I could, because it just seemed to extend the life of it.

We didn’t have a lot of time to make a lot of remakes in that first year or two, because we threw every puppet we had from whatever Jim had done early on — I mean, that’s when Yorick appears again, and all those puppets come out of those boxes and into the show in one way or another. Fortunately, Jerry Juhl had been a writer for Jim for all those years, so between the two of them they knew the history of what they had to work with in terms of coming up with bits for the early shows.

TP: Do you have any opinions on the current look and design of Miss Piggy? Some of the fans on our forum have had some criticisms, like her ears are the wrong shape, or her eyes are the wrong size…

TP: Do you have any opinions on the current look and design of Miss Piggy? Some of the fans on our forum have had some criticisms, like her ears are the wrong shape, or her eyes are the wrong size…

BE: People age. (Laughs.) People change. Even pigs. You know, I think so much of it is the group effort — the writers, the performers — and there are people who are looking at Miss Piggy today who never saw her as the original…

I don’t have a problem with things changing. I just want them always to look as good as they can, to perform as well as they can, and to be interesting to watch, and as whimsical as they were initially. If they can do that, I don’t have a problem. Of course I will sit back and go, “Hmm… Now, I wonder…” but I think if they have a life and they’re successful, that’s fine with me. Why shouldn’t everybody else have a chance to have fun?

But I would say, making duplicates is probably not as much fun as doing the originals or starting with something new, and I’m hoping that there will be really wonderful additions and things coming up, because you know, all these characters will be out for everybody to see again in November with the new movie. I’ll be watching the blog to see what everybody thinks about that!

Note: As you’ve no doubt deduced by now, this interview was conducted before the release of The Muppets. Thanks to Bonnie Erickson for her time, insight, and memories! Click here to lose your concentration on the Tough Pigs forum!

by Ryan Roe – Ryan@ToughPigs.com