Muppet Gals Talking is a series of interviews and spotlights on female producers, puppeteers, puppet builders, and other creatives who’ve worked with the Muppets. This series is researched, written, and expertly produced by journalist L. Drake Lucas.

Natasha Lance Rogoff had just screened her latest documentary in 1993 when Gary Knell, former head of Sesame Street, walked up to her to ask if she would produce a Sesame Street for a Russian audience.

Natasha found it surprising and laughable.

“What about my film makes you think I could do this?” she remembered asking.

The film Knell had just watched was a documentary about the collapse of the Soviet Union. Natasha had spent two years imbedded with hardline communists. She didn’t know children’s television and didn’t particularly know children, having had none of her own yet.

She had, however, developed a knowledge of working in Russian TV while making documentaries during the period of the declining Soviet era. Working under the radar, at times followed by the KGB, she was drawn to exposing injustice in a country where freedoms such as speech, movement, and travel were restricted. She saw journalism as serving an important role in telling the stories of people who were not allowed to tell their own stories.

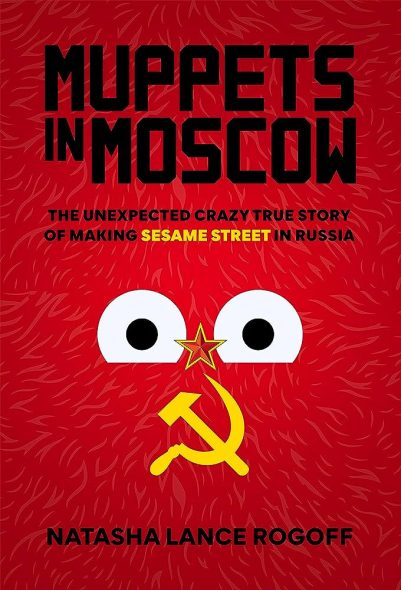

As she chronicles in her book, Muppets in Moscow, she did end up bringing Sesame Street to Russia, where it was known as Ulitsa Sezam. It is an unimaginable series of setbacks – way more assassinations and backrooms full of oligarchs and money stuffed in bras than one would expect for a Muppet production – that somehow led to a beloved television show. Part memoir, part suspense story, part history lesson, it is ultimately a story of hope with a poignant relevance for today’s world.

Natasha’s early connection to Sesame Street was minimal. Born in New York, she was 9 when the show debuted in the United States. She knew of it and admired the creativity and sophistication it brought to a children’s show, but she was older than the target audience.

She remembers instead being fascinated by a book of Russian fairy tales she had picked up – beautiful pictures and dark stories. Her grandfather left Belarus for the United States in 1912 and she grew up hearing his stories of where he was from. She was drawn to Russian authors, such as Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and the “cruelty and absurdity” of Gogol. After studying Chinese history at UC Berkeley, Natasha went to Columbia University for grad school and studied Soviet foreign policy, ending up as an exchange at Leningrad University in 1982.

Natasha described how everything Americans had been exposed to about the Soviet Union was influenced by propaganda and limited access.

“It was different when you go there and meet regular people who become your friends,” she said. “I understood society on a whole other level that was much deeper.”

Natasha became immersed in the complexities – the attempt for government control countered by an underground culture where people lived against the norms. She wrote and published articles on rock and roll musicians denied the right to produce, sell, or perform in public. She wrote about the persecution of Russia’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community.

She learned how to sneak material out of the country. And she learned how to use society’s assumptions for her own purposes. Because Russia was such a patriarchal society, it had a habit of underestimating women and thinking they were harmless, a bias she found useful when she needed to get away with something, like filming in a military installation.

That was her experience when she was tasked with putting together Ulitsa Sezam. Ultimately, she was drawn in by the impact a successful show could have by modeling a world that was more open, kinder, and freer. She called it “seductive and terrifying.”

“We felt the stakes were high,” she said. “We were trying to change the future for millions of children and future generations.”

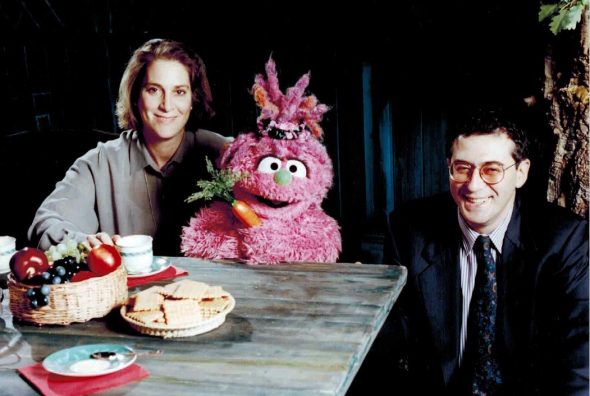

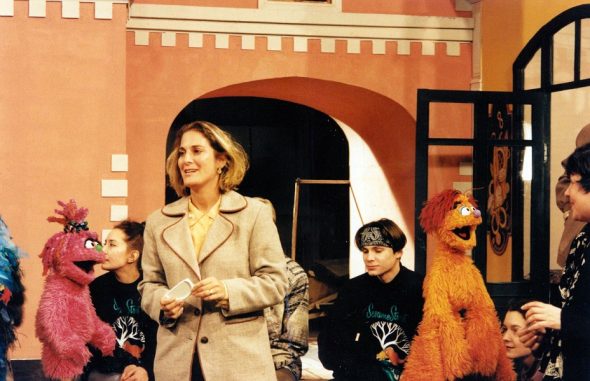

Natasha’s role as executive producer was to assemble and lead a team of more than 400 artists and media professionals. She was also co-director, with Vologya Grammatikov, because she was deeply involved in the creative development of the show – reviewing every script, music for the show, and set design in addition to the more logistical and business aspects of the show, all made more difficult because of the budgetary, political, and cultural barriers.

She had been in plenty of media rooms that were “99.9 percent male,” so she deliberately hired women as more than half her staff, including producers and writers. The head of music, the set designer, the art director, and the chief coordinating producer were all women. They had more women in key positions than had ever happened in Russian TV production. They also made an effort to hire people from different generations and from across the region, including from Ukraine, Armenia, and Georgia.

(bottom row, from left) Uliana Savelieva, Tamara Pavliuchenko, Natasha Lance Rogoff, Robin Hessman, Vika Lukina, and Misha Davydov. Author’s collection.

A variety of voices in the room strengthened the conversations and decisions, including the development of Businka, the female Muppet character. A number of older writers wanted Businka to be dutiful and docile. Initial conversations indicated she would not be playing soccer or other sports with the boys, but the younger generation of female writers thought differently. The character ended up fiery, active, and mischievous.

Natasha remembers anticipating that the Russian public might react strongly against the Muppet characters for being too wild or not obedient enough. Celebrating everyone’s unique, authentic self was not the predominant message of the USSR. In one telling scene from her book, they had to change the way they test segments with a child audience to see what interests them. In America, children just wander off or start doing something else when they aren’t into the segment. In Russia, the children sat watching the TV as told and would only move around or leave their place when the adults left the room.

The concern about whether the audience would embrace the Muppets was unnecessary. People responded to the characters with warmth and they became hugely popular.

“It was a time of incredible difficulty,” Natasha said. “There were food shortages, the medical system was collapsing, and there was great political instability. No one was sure if the country would remain open.”

The goofy and soulful Muppets were a welcome presence. Through them, the show was able to create a more open playground for children. Natasha said she aimed to counter the “no” and make children feel like they could try things and make mistakes.

While the show’s production ended in 2010, it has a lasting legacy. As Natasha travels the world, she hears from many adults who grew up on the show about how important it was to them and how it changed the way they viewed the world. The showed aired across 11 time zones and was seen by tens of millions of children.

“I knew it was a remarkable story,” she said. “Our success was not at all expected. Most people thought we would fail.”

Luckily, she kept notes. Lots of them. She wrote in her journal and kept copious documentation of the curriculum seminar where video was also shot and transcribed. She kept boxes and boxes of her material for 30 years in anticipation of writing a book.

With the Covid-19 pandemic, working on documentaries was shelved, so she turned to the 30 boxes of Ulitsa Sezam to fulfill a dream she had had since 12 years old – to be a writer. In addition to her archives, she conducted almost 50 interviews with Russian and American colleagues from the time. Luis Santiero, celebrated writer of Sesame Street who trained the Russian writers, shared his journals from the time, including notes written after each session with the writers.

She also felt it was time to write the book because she sensed the rising danger of the misunderstanding between Russia and the West, including the Russian invasion of Crimea and Russian tampering with US elections. She thought about the challenges she had faced in producing Ulitsa Sezam, but how they had also found commonality despite their differences in the hope that Ulitsa Sezam could model a freer, more open world.

“The creation of Ulitsa Sezam was a shining moment of collaboration and the Muppets a key part of encouraging tolerance, openness, and laughter,” she said.

She chose to write the book as a memoir partly through the understanding of how her background and personal experience – including being a woman focused on injustice and being Jewish – influenced her perceptions. She also wanted the story to be genuine and personal, so that people could relate to it.

“I hoped that by telling this personal story that readers (and especially young women) would see themselves in this narrative and embrace their own power as daring, compassionate actors in the world, willing to take risks in the hopes of helping others to live in freer societies,” she said.

Unfortunately, the region is again facing turmoil. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has led to a brutal war. Russia has increasingly become repressive against its own citizens, arresting those who speak out against the war or government actions. A number of Natasha’s former colleagues had to flee Russia after speaking out. Those that stayed have been forced into silence and don’t have the same opportunities for work that they used to.

Yet, Natasha has hope. She saw the Soviet Union collapse, ushering in a period of openness before society closed again. She believes there will be a time when Sesame Street can return. She saw things change in Russia before, a place, she said, where nothing is constant.

“I believe in the power of creativity and laughter. It always wins out in the end,” she said. “If anything, that’s what I learned from the Muppets, and it has served me well in my life.”

Pick up your copy of Muppets in Moscow wherever you buy books! Click here to learn from the Muppets on the Tough Pigs forum!

by L. Drake Lucas