What happens when you close your eyes and whisper the words Atlanta, Georgia? Do you see peach trees? Streets named after peach trees? The World of Coke’s infamous Beverly sample flavor? Streets named after numerous battles over peach trees? Matlock?

What happens when you close your eyes and whisper the words Atlanta, Georgia? Do you see peach trees? Streets named after peach trees? The World of Coke’s infamous Beverly sample flavor? Streets named after numerous battles over peach trees? Matlock?

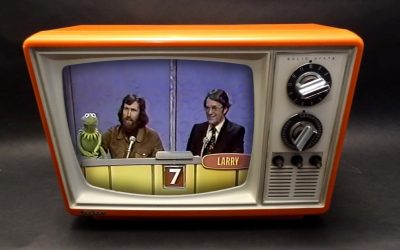

The first thing I learn when I visit is that the Jim Henson exhibit, much like an eager teenager dolled up for the big dance, hides treasures so dear that the staff will unabashedly question your intentions. “Photography inside is not allowed,” I’m reminded several times by otherwise friendly folks. I resort to photographing the teasers outside — a Kermit puppet, an iconic photograph of Jim and Kermit, a nifty shot of Kermit and Piggy as Rhett and Scarlett — and scribbling pages of notes within. Even as I exit, clutching my notebook, a nervous docent asks, “You didn’t… draw any pictures, did you??”

The first thing I learn when I visit is that the Jim Henson exhibit, much like an eager teenager dolled up for the big dance, hides treasures so dear that the staff will unabashedly question your intentions. “Photography inside is not allowed,” I’m reminded several times by otherwise friendly folks. I resort to photographing the teasers outside — a Kermit puppet, an iconic photograph of Jim and Kermit, a nifty shot of Kermit and Piggy as Rhett and Scarlett — and scribbling pages of notes within. Even as I exit, clutching my notebook, a nervous docent asks, “You didn’t… draw any pictures, did you??”I couldn’t possibly recreate that room in crude sketches with any sort of accuracy. Bright, angular text panels decorate the walls, along with classy enlarged photographs, and some of Jim’s original doodles. Along the back wall, monitors play a looped reel of old clips alongside a slide show of production photos. What immediately leap out at me, of course, are the puppets.

Over half a dozen puppets wave at visitors from glass cases. Since multiple players own the rights to these characters, the Center and the Jim Henson Legacy keep a close watch on the goings-on. What I forfeit in souvenir photographs, however, I more than recoup in the gift shop later on.

Over half a dozen puppets wave at visitors from glass cases. Since multiple players own the rights to these characters, the Center and the Jim Henson Legacy keep a close watch on the goings-on. What I forfeit in souvenir photographs, however, I more than recoup in the gift shop later on.

Moving clockwise around the room, I first examine Rowlf, who appears next to a framed picture of Lassie. Some of the text next to him describes the character’s history, as well as an explanation about live-hand puppets. The Swedish Chef and Dr. Teeth share one long glass case, which also contains vegetables (none with faces, sadly), a meat cleaver, a rubber chicken, and a painted wooden keyboard for the Doc.

I’m beginning to notice a Henson-as-a-man and Henson-as-a-performer theme, which is no surprise given the nature of the whole project. Most of the text panels manage to connect their puppet to Jim’s groundbreaking innovations using puppets on television, or his development as an entertainer. The Muppet performers receive a fairly decent shout-out; a bunch of head shots (I immediately fall in love with a photo of Richard Hunt holding Scooter and wearing a cowboy hat) surround a quote about how the players used to bounce off each other. Also typical for these text panels is some conclusion about how more such excitement is on its way, come 2012.

Along one corner of the back wall covered with monitors, I find touchable samples of puppet-building materials; this, combined with the clip reel, should be enough to appease younger visitors while their parents geek out over the pictures and text. (I say “younger visitors” because my family, by this point, has tired of watching the clips roll three times while I take notes — and has pushed ahead to the Salem the Talking Cat exhibit outside.) While the slide show flashes photos and sketches, the reel itself features a fitting mix of everything from familiar spots like Rubber Duckie to bits that casual fans might not have seen before, like a Purina Dog Chow commercial.

The Dog City corner switches up the format with a formal little flip book of character sketches; nearby, Jim’s counterpart from the Country Trio strums a banjo, next to a textual tidbit explaining that while Jim never played the banjo, he would have liked to. I can’t stop looking at a pillar featuring a lovely floor-to-ceiling picture of Frank, Jim, and Richard as Bert and Ernie. In wandering around the exhibit named for Jim Henson, apparently I’ve been itching for more frogs and dogs and bears and chickens and things: more mentions of everyone who worked with Jim, behind-the-scenes interactions, perhaps one or two Muppets not performed by Jim Henson. Maybe I should stop taking notes.

The Dog City corner switches up the format with a formal little flip book of character sketches; nearby, Jim’s counterpart from the Country Trio strums a banjo, next to a textual tidbit explaining that while Jim never played the banjo, he would have liked to. I can’t stop looking at a pillar featuring a lovely floor-to-ceiling picture of Frank, Jim, and Richard as Bert and Ernie. In wandering around the exhibit named for Jim Henson, apparently I’ve been itching for more frogs and dogs and bears and chickens and things: more mentions of everyone who worked with Jim, behind-the-scenes interactions, perhaps one or two Muppets not performed by Jim Henson. Maybe I should stop taking notes.

Fortunately, I’ve arrived at the Sesame Street display, which mimics the Sesame Street set and has a brighter, more cartoonish feel than the rest of the exhibit (the Henson Legacy includes Ernie in their handful of pictures from the exhibit, if you’d like a better idea). Next to Ernie’s display case, a door explains Joan Ganz Cooney’s vision for the show, and how the Sesame Street puppets subsequently came about. Above a sill adorned with cardboard tulips and sunflowers, a window quotes Jim Henson describing how people might respect and care for each other. I particularly like the picture of a stained glass window showing Jim and Frank as Ernie and Bert, next to a tidbit explaining that Jim had originally intended to play Bert, while Frank would play Ernie, before the two switched roles.

Before proceeding out to the main wing — and I could write a whole other article about how much I loved the Center’s permanent exhibit, full of wacky interactive puppet mechanisms and a whirlwind tour of puppetry around the world, not to mention a Skeksis and two Swinetrek crew members — I stop at the La Choy Dragon‘s case and read a letter of appreciation from a producing advertising executive.

Before proceeding out to the main wing — and I could write a whole other article about how much I loved the Center’s permanent exhibit, full of wacky interactive puppet mechanisms and a whirlwind tour of puppetry around the world, not to mention a Skeksis and two Swinetrek crew members — I stop at the La Choy Dragon‘s case and read a letter of appreciation from a producing advertising executive.

“What a pleasure to work with people whose views of the world are unrestrainedly mad,” writes Mr. Grisham. “These commercials are going to make a lot of people happier for having seen them.” I stop in my tracks. So many of my Muppet fan friends and I have struggled to embody just that, singing and dancing and making people happy in any way we can, for as long as we can remember. Even in the commercials he made in 1965, years before he would weave his vision into his own television shows, Jim Henson was already living that dream. Making people happy came naturally to him. I leave on that note.

Click here to discuss this article on the Tough Pigs Forum!

by Michal Richardson