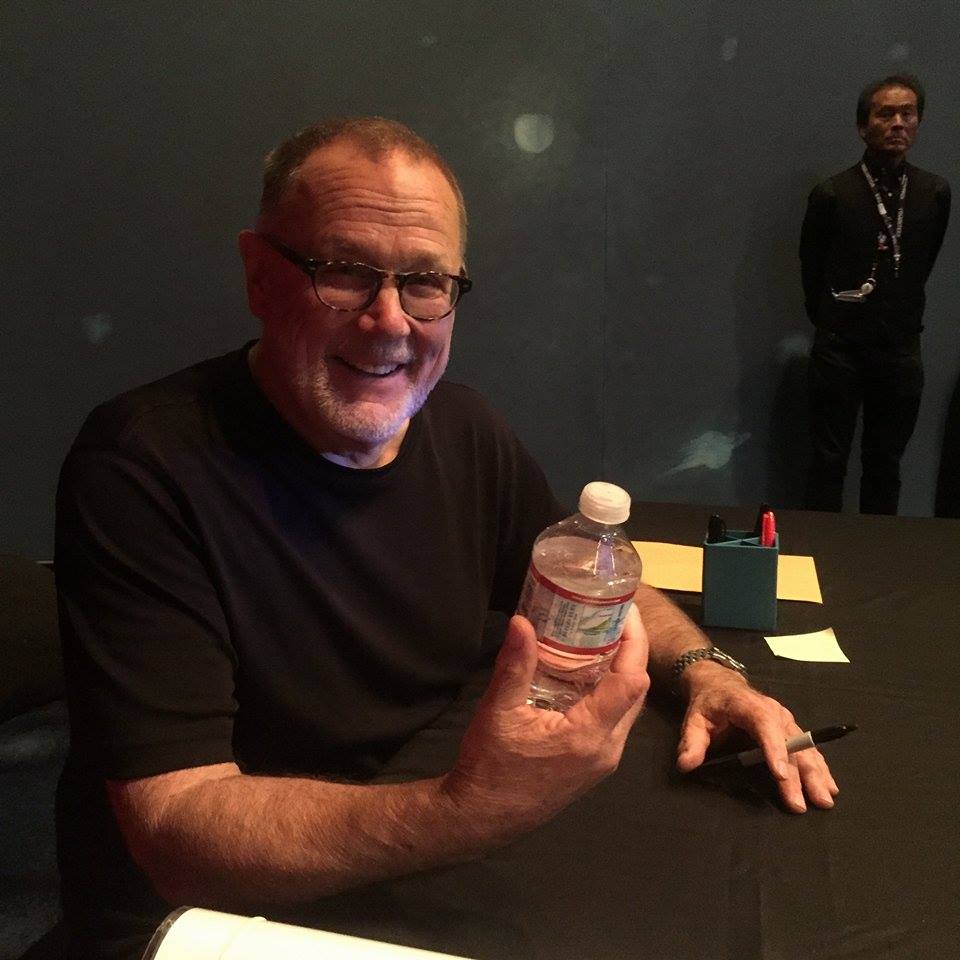

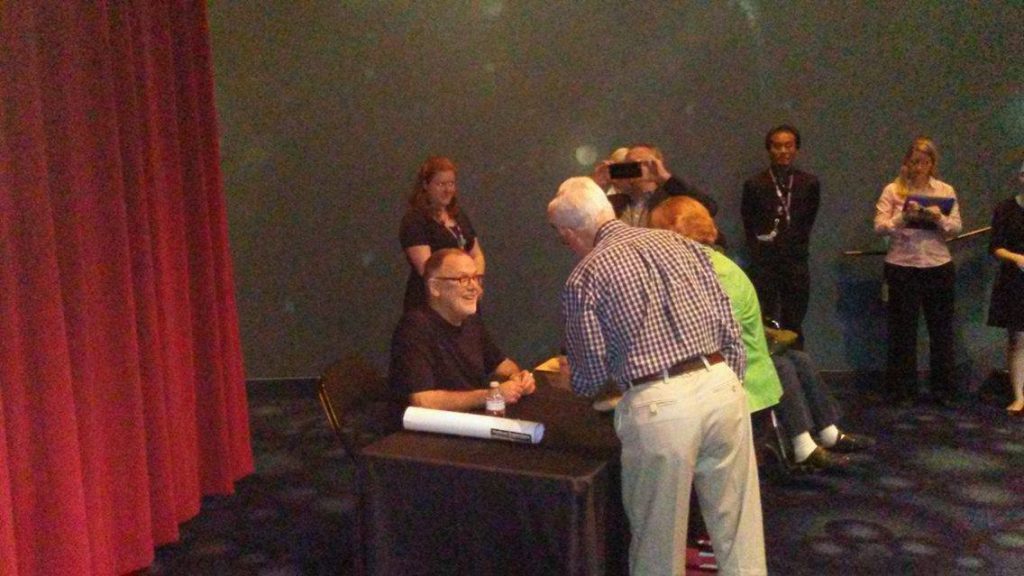

Dave Goelz recently made an appearance at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco. Tough Pigs’ own Danny Horn and James Carroll were both there, and provided us with some great info and photos from the event. After reading this report, you’ll feel like you were there! Thanks, Danny and James!

The Walt Disney Family Museum is one of the great treasures of San Francisco, a big two-story building that tells the story of Walt’s life and work through engaging and interactive exhibits. Seriously, you should go; it’s bigger and cooler than you’re imagining right now. Come to San Francisco. Not right now, finish reading the article. But after that, you should go to the museum. They’re currently running “Wish Upon a Star: The Art of Pinocchio“, a special exhibit on the making of Disney’s second animated film, Pinocchio. The exhibit runs until January 2017.

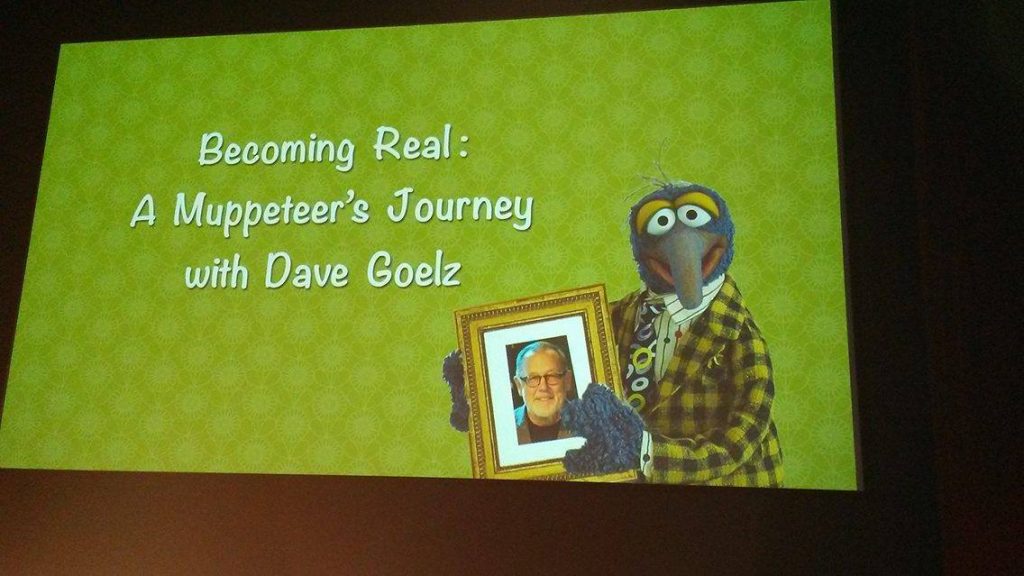

The museum hosts a guest speaker every month, often related to the current exhibit, and this month, the talk was “Becoming Real: A Muppeteer’s Journey with Dave Goelz.” Pinocchio is the story of a puppet that becomes a real live person, which happens to be one of Dave’s specialties.

Dave was very happy and upbeat, sharing fond memories with an appreciative crowd. The Electric Mayhem’s live appearance at the Outside Lands Music and Arts Festival was just a week earlier, and he was still really jazzed up about the experience, bringing it up several times as an exciting moment. He didn’t mention the Muppets TV show, and nobody asked about it.

I took a lot of notes during the talk, as I do, and what I’ve got here is a loose paraphrase “transcript” of Dave’s presentation and the Q&A.

Walt Disney’s Pinocchio is about becoming a real live boy, how a puppet earns its humanity. At the Muppets, we try to do the same thing, taking a puppet and making it real. I’ve been doing this for a long time, and I thought I’d take you inside the Muppet culture, and inside my skull for a while.

I grew up in Burbank, just two miles from the Disney studio. I had no access to it, of course. But I saw the movies, as everyone did, and I went to Disneyland. As a seven year old, I watched The Mickey Mouse Club and thought, gosh, I wish I could be on that show. I had no knowledge or talent, so obviously that didn’t happen.

I saw Pinocchio when it was in theaters in 1954, when I was eight. I remember it as a pleasant experience, but I couldn’t really recall much about it. But when I was asked to give this talk, I went back and watched it, and I recognized it as a masterpiece, with beautiful, amazing characters. The animation and composition are just extraordinary.

The movie starts with little set pieces that introduce each of the characters. Geppetto is working all day and night, Figaro the cat spars with the goldfish Cleo, Jiminy Cricket comes into the shop and warms himself in front of a coal. It introduces a world that you want to stay in. I couldn’t believe how great it is.

I was brought here today as a bit of a Geppetto figure, but I wasn’t at the time. Geppetto wanted a child so badly that he made one out of wood. I didn’t, because I was so excited about working with Jim, traveling all over the place, and all I wanted to do was work. I didn’t think about having kids then; it would get in the way of the work.

I was brought here today as a bit of a Geppetto figure, but I wasn’t at the time. Geppetto wanted a child so badly that he made one out of wood. I didn’t, because I was so excited about working with Jim, traveling all over the place, and all I wanted to do was work. I didn’t think about having kids then; it would get in the way of the work.

Really, my first exposure to character creation was my dad, who would tell me stories about his youth. He grew up in a small town in California, and I heard all these stories about the characters in town. They were like Mark Twain stories — he lived in California for a time, and wrote “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” here. My dad’s stories gave me a clear view of human folly — all the foibles and accidents — and I grew up loving that.

When I grew up, I became an industrial designer, working in Silicon Valley, although it was very different back then. I worked for Hewlett-Packard. It was a great company, and so benign. During a recession, they needed to cut their payroll 10% — but instead of laying people off, they cut everyone’s wages 10%, from Hewlett and Packard at the top, all the way down. It wasn’t enough money to throw anybody into a panic. They held it there until natural attrition brought the number of employees down, and once enough people had left, they brought everybody’s salaries back up to what they were. It was inspired.

But I didn’t fit in. Everybody was split up into verticals, and I didn’t want to grow vertically. I was like ivy. I wanted to grow horizontally; I wanted to learn about everything. But if you went horizontally, you’d intrude into other people’s territory, and you’d get smacked, and go back to where you were.

HP made very important products, but I felt it was just an intellectual exercise. It didn’t feel real to me. I needed to find something else that I could feel passionate about. Other people at the company told me, get out while you can! But I didn’t know what I wanted to do yet.

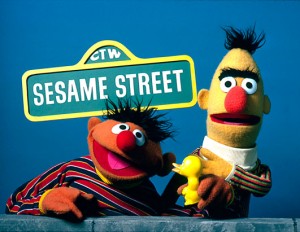

By coincidence, I happened to accidentally watch Sesame Street. I just caught it one day. One of my close friends had a job at a PBS station in LA, and he was producing a TV program. I thought, if Mark’s producing a show, I ought to get my TV out of the closet and watch it. I had this tiny black and white television, which I kept in the closet. It was the 70s, nobody watched TV anyway. I never got around to seeing Mark’s show, actually.

It was Saturday morning when I got the set out of the closet, and when I turned it on, Sesame Street was on. I’d been a Muppet fan for years — I watched them on Ed Sullivan and other programs, and I loved what they did. This was the first time I saw what they were doing on Sesame Street.

The PBS station showed it every day, and on Saturday mornings, they ran all five episodes in a row, and I found myself just sitting there and watching all five hours of Sesame Street. The next Saturday, I did the same thing, and the next. I couldn’t stop, because I couldn’t believe the spirit and the honesty of the characters. They were vividly real to me. I loved them.

By the way, you can put your chicken hat on, if you want to. (One member of the audience had a homemade hat topped with a fuzzy Muppet-style chicken, which he was holding on his lap.) Wow. That is a very impressive chicken hat. I’ve seen a lot of chicken hats in my life, this is the best I’ve ever seen. (A few minutes later, Dave gave the man permission to take the chicken hat off.)

So, the characters on Sesame Street. Bert was loud, and high contrast — harsh black hair, bright yellow skin, a single eyebrow that cut across his face. Very vertical, and upright. Ernie was low contrast, horizontal. He had an easy laugh, and he wanted to relax and have fun. Bert’s voice was tight; Ernie’s was soft and lyrical. They’re complete opposites, and as a result, Ernie teases Bert relentlessly.

So, the characters on Sesame Street. Bert was loud, and high contrast — harsh black hair, bright yellow skin, a single eyebrow that cut across his face. Very vertical, and upright. Ernie was low contrast, horizontal. He had an easy laugh, and he wanted to relax and have fun. Bert’s voice was tight; Ernie’s was soft and lyrical. They’re complete opposites, and as a result, Ernie teases Bert relentlessly.

One thing seized me, and I got really curious — who are the people who make this? There’s puppeteers, of course, but there must be producers, and writers, and costume designers — and they’re all on the same page, putting this together. Ernie and Bert are like Laurel and Hardy, they’re a classic comedy duo. Just unbelievably good. So this is what I saw.

(Dave shows a clip: Ernie and Bert doing the “pot on your head” sketch.)

God, I never get tired of those two — Jim Henson as Ernie, Frank Oz as Bert.

So that was about 1972, and a year and a half later, I’m sitting at a workbench at Henson Studios in New York. And it really happened through obsession and compulsion. I didn’t want to go to New York, I didn’t like the place at the time. Besides, I had no training, I was an industrial designer. But I was drawn there by a magnetic force. I couldn’t stop. And I got lucky. Once in a while, if you really love something, you can figure out how to do it.

That brings me to the next part of the talk: how we create characters.

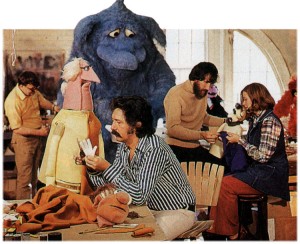

With the Muppets, nobody made characters alone. It was always an interaction between Jim, the puppeteers, the writers, the workshop, and anybody in the studio, anyone who was around. If you had an idea, no matter who you were, people felt perfectly comfortable telling Jim. He would stop, and listen, and then make a decision based on whatever his opinion was. Everyone was very open.

Each performer has their own way to make characters. We didn’t even talk to each other about how we did it; it was just play. My technique was that I would always make characters based on one of my flaws, something I would be embarrassed by. This gave me infinite material.

There’s clumsiness, which is a huge fear, especially for kids. Uncle Matt on Fraggle Rock is a character based on that. Fraggle Rock took place underground, but one Fraggle went exploring. He was originally supposed to be about misperceiving things — seeing something in the human world, but misunderstanding what it is — but that wasn’t enough of a hook. The scenes were effective, but I was having trouble making them funny. I had to do something with Matt that made it funny, and physical clumsiness was the way to do it.

I also added later a denial system, where he could never admit he was making a mistake. But he made mistakes all the time, because he was misperceiving things. So he had an intellectual flaw, a physical flaw and an emotional flaw.

(Another clip, from “Uncle Matt Comes Home”: Matt enters the workshop, where a camera is set up by the Fraggle hole to capture a shot of any creature entering the hole. Matt moves the camera, then wakes up a sleeping Sprocket as he trips on the camera wire. As he leaves the tunnel to greet his nephew, he hits his head and trips, turning a somersault with his feet flying up into the air.)

(Another clip, from “Uncle Matt Comes Home”: Matt enters the workshop, where a camera is set up by the Fraggle hole to capture a shot of any creature entering the hole. Matt moves the camera, then wakes up a sleeping Sprocket as he trips on the camera wire. As he leaves the tunnel to greet his nephew, he hits his head and trips, turning a somersault with his feet flying up into the air.)

When we shot that — I wanted to find new ways to make him clumsy. I saw Steve Whitmire leaving the studio, and I said come back for a second, and told him briefly what I wanted to do. Steve is a master puppeteer, and he could figure out anything. When I made Matt trip, Steve had Matt’s legs — which were actually a separate part of the puppet — and he did that little flip behind me. That’s how we did that little moment.

Another flaw is obliviousness. Nobody wants to be outside the joke.

(Clip from The Muppet Show: Dr. Bunsen Honeydew presents his new invention, Bunsonium. He has Beaker drink the liquid, which makes Beaker’s head deflate.)

Bunsen Honeydew was kind of drawn from my experiences at Hewlett-Packard. Sometimes engineers would get caught up in the minutia, and miss the big picture.

Another fear that I have is foolishness — being caught out, and being embarrassed.

(Clip: Gonzo reciting Shakespeare while hanging by his nose from a feather boa.)

And then the worst of all is stupidity — when you just don’t know something at all.

(Clip from The Great Muppet Caper: Beauregard picks up Kermit, Fozzie and Gonzo, and drives in circles. He takes them to the Happiness Hotel, driving straight through the front door and into the lobby.)

When we shot that driving scene, it was early in the morning, and we were on Piccadilly, right in the middle of London. And then the hotel was a different location. It was really kind of scary — Jim, Frank and I, on the floor of the car, lying on cushions — and we couldn’t see where we were going. We just had a radio monitor. There was a stunt driver wearing a Beauregard outfit driving the car, and we made that turn — there was a balsa wood door frame, and we hit that door at 20 miles an hour. We were saying, are you sure you can line this up right? You’re sure you can hit that door? Jim was never worried about things like that, he loved it. He just said, oh, this will be great.

When we shot that driving scene, it was early in the morning, and we were on Piccadilly, right in the middle of London. And then the hotel was a different location. It was really kind of scary — Jim, Frank and I, on the floor of the car, lying on cushions — and we couldn’t see where we were going. We just had a radio monitor. There was a stunt driver wearing a Beauregard outfit driving the car, and we made that turn — there was a balsa wood door frame, and we hit that door at 20 miles an hour. We were saying, are you sure you can line this up right? You’re sure you can hit that door? Jim was never worried about things like that, he loved it. He just said, oh, this will be great.

So I want to talk about the Muppet culture, the organization that Jim built. The work that we did was obviously very intellectual, but also very emotional, and we were devoted to it. When I went to work for Jim, I worked ten times as hard as I did at HP, very long hours. Jim had something innovative at the workshop — there was a little side room with a bed, and if you needed to rest, you could take a nap in there. Everybody used it. Jim was forty years ahead of Google. And the result — we worked longer hours, and we were utterly dedicated.

In this culture, there were always new challenges, and plenty of horizontal growth. I remember once when we were shooting The Muppet Show, Jim asked me to choreograph this number with the Gills Brothers, a barbershop quartet of fish. There were four fish, with very serious expressions, and little fins. Jim had to go work on something else, so he told me do this choreography, and then he’d come back, and I could teach it to everyone before we shot it.

So I came up with this choreography, but I didn’t know what to do at the end, so I decided it was a die ending. At the end of the song, they would just fall backwards and die. When Jim came back, he said what’s a die ending? I said it’s something we’ve never seen in choreography before. It’s innovative. So we had this silly fake argument about it, and we ended up not doing it. That’s what it was like — it was always about playing, and we’d end up in these little psychodramas.

So I came up with this choreography, but I didn’t know what to do at the end, so I decided it was a die ending. At the end of the song, they would just fall backwards and die. When Jim came back, he said what’s a die ending? I said it’s something we’ve never seen in choreography before. It’s innovative. So we had this silly fake argument about it, and we ended up not doing it. That’s what it was like — it was always about playing, and we’d end up in these little psychodramas.

At the workshop, there was a culture of practical jokes, scares, sneak attacks. Jerry Juhl and Frank Oz had this long-running war involving a cherry danish. One day, Jerry handed Frank a cherry danish, and Frank gave it back to him. A few days went by, and Jerry slipped it back to Frank somehow, and the danish started on this journey, passing back and forth between them in creative ways. The danish got stale. It got hard. Eventually some mold was growing on it. And it was still going back and forth. I don’t know how long it went on. Then it got lost at some point; it just ceased to exist. Eventually Jerry Juhl made a board game for Frank, called The Cherry Danish.

Back in my early years at the Muppets, we were doing a shoot on a Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass special. Jerry Nelson pulled this little knot out of the wood, and he handed it to me. I asked, what is this? And he said, it’s a knotty problem. So that knot went back to Jerry, and back to me — for 25 years, we’d find ways of giving it back to the other. It ended up, I built a little wooden box for it, with a red velour insert. A beautiful little presentation. I mailed it to him. I never saw it again. It might still be in their house, in Cape Cod.

And then there was Don Sahlin, the master, the greatest of all puppet makers. And he was an absolutely dedicated prankster — he would do scares constantly. It wasn’t like hiding behind the door and jumping out at people, it went way beyond that.

At the workshop, there was a little bathroom — and if you were the first one in, you had to go into this bathroom to flip the circuit breakers, to turn on the lights and the air conditioning and everything. So Don, who worked in the evening when no one was there — once he took a dress frame and draped it with this dark, murky fabric. He made this hideous monster, with a string attached to the door, so when the door opened, it would turn slowly to face you — Jim was the first one in that morning. It scared the hell out of him.

Another thing Don would do — he’d take a little bolt, and attach some gray or brown fur with a little piece of yarn. Then he’d buy a rubber band on a reel — 500 feet of rubber band — and attach it to the little mouse. He’d put a pin in it, and hide it behind the furniture. And then he’d string the rubber band carefully around the room, wrapping it all the way thorugh the desks and along the wall, leading to a little washer under his desk with a ring. Later on, when everyone was working, he’d pull the ring, and the mouse would go darting around the workshop.

We had a bookkeeper at the time, a big blond Greek woman, a wonderful lady — but she didn’t like mice. So there were so many times — Don would pull the string, she would go up about a foot, the mouse would go by underneath, and she would come back down.

He did it to me, too. We all worked at desks, all covered in foam and fabric, papers and sketches. I came in one morning, got some coffee, sat at my desk, working quietly — and all of a sudden, the whole thing exploded. Don had put a dynamite detonator under some of the stuff on my desk, with a wire running along the whole baseboard, and a doorbell button under his desk. So when he was ready, he’d just push the button and watch the result.

Don and I got into this long-running battle, and one day, I thought, I’m going to win this battle. I will scare him so much that it will kill him. And I’ll win!

When you were leaving the workshop, what you would do is flip the circuit breaker, turn off the lights and the air conditioning, take the elevator down, and then lock the outside door when you went out. Don would work from noon to four, then go out for a while, and come back and work eight to midnight.

When you were leaving the workshop, what you would do is flip the circuit breaker, turn off the lights and the air conditioning, take the elevator down, and then lock the outside door when you went out. Don would work from noon to four, then go out for a while, and come back and work eight to midnight.

So I went back about 7:00, locked the outside door behind me, took the elevator up, and kept the lights off. I went into the bathroom and sat on the toilet, wearing this big black cloth. The idea was that when he came in and reached for the circuit breaker, there would be a human hand on it. And he would get so scared that he would die.

But it was so hot and humid in there; the air conditioner was off. I waited until 8 — no Don. I kept waiting — still under this heavy black cloth, sweating like crazy — 8:30, 8:45, 9:30, 10:00. I finally realized – he’s not coming back tonight. So Don lived.

But the most subtle was Jerry Juhl, our head writer, and the sneakiest, most insidious person of the bunch. On Fraggle Rock, I did all these outside shoots with Uncle Matt, and Jerry would write me into these horrible situations — it looked great on camera, but it was not good for me. He’d send Matt to the city dump to sit down on this huge pile of garbage, because he knew that I would be sitting there, under the garbage.

Jerry was a very affable guy, on the surface. But he’d write this stuff, and I’d go out and have some terrible experience, and he’d just sit quietly at his desk, thinking about me. He’s writing the next show, thinking, Oh, Dave must be under the garbage right now.

He did another one in a chicken coop, with me laying on the floor and maybe 10 to 12 chickens. I don’t know if you’ve been around chickens, but their poop smells like ammonia. And there I am, lying down in it, and Jerry’s sitting at his desk, smiling.

Then he wrote one with a 500 pound sow, in a pen, again, with me on the ground. Before we started filming, the zookeeper said if she starts to roll over, GET OUT. And there’s Jerry, at the desk, thinking, he must be right under that pig right about now.

And then — he knew that I didn’t like roller coasters. I didn’t want to be the one statistic, the guy who just blew right off the roller coaster and went flying. So Jerry wrote a scene with Traveling Matt on a roller coaster, and we shot it on this big wooden roller coaster. I had to ride it 13 times. I was sitting next to Matt, working the puppet with my right hand and then pretending to be a completely different person sitting next to him. And I had to look like I was having a great time, while Matt was scared out of his mind. That was hard to do, actually, because we usually make the same expression as the puppet does. So I had to just smile as the puppet went crazy. Of course, Jerry was sitting at his desk, all innocent. But it backfired on him, because I really like roller coasters now.

Really, Jerry Juhl was all heart — a very funny writer, but it was always better if the material meant something. He believed in the same kind of things that Jim did — that people are basically good, we should celebrate diversity, let’s be around other cultures.

When Jerry, Susan [Juhl] and I met — for some reason, we just gravitated to each other. We laughed a lot, and had a lot of fun, despite how cruel he was to me. And Jerry saw me growing and changing, and ended up incorporating that into Gonzo. The character evolved. Jerry didn’t want to know too much about it, or think about it with his brain; it just happened unconsciously.

Gonzo started on The Muppet Show as a loser, with downcast eyes, never feeling like he belonged. And that was me — I was completely foreign to this environment, all of a sudden I’m in a room and somebody walks in, and it’s Danny Kaye, or Sylvester Stallone, and I’m thinking, these are huge stars, why am I here? I would just duck out of the room.

Gonzo started on The Muppet Show as a loser, with downcast eyes, never feeling like he belonged. And that was me — I was completely foreign to this environment, all of a sudden I’m in a room and somebody walks in, and it’s Danny Kaye, or Sylvester Stallone, and I’m thinking, these are huge stars, why am I here? I would just duck out of the room.

So in the beginning, Gonzo looked like this:

(Clip: Gonzo singing “My Way” on The Muppet Show as his farewell performance, ultimately breaking down and being led offstage by Kermit.)

I forgot to tell you what that was about — it was an episode where Gonzo decided to go to Bombay to become a movie star. It was a really heartfelt scene, which I was terrified to do — I didn’t want real emotion, I just did silly things. Gonzo was leaving, but he found that he couldn’t really leave, because he loved these people so much. That was his pathetic loser phase.

They kept telling me to make him more upbeat, so I made this new eye mechanic that gave him a different expression. That started the next phase, which was a little more manic.

(Clip: Gonzo sings “Dancing With Myself” on Muppets Tonight, with a dozen Gonzos.)

Then I kept evolving as a human being, and Jerry saw all this. After Jim died, our first feature film was Muppet Christmas Carol. The story was written by Charles Dickens, and Jerry wanted to include all the Dickens prose; the language was so beautiful. But he didn’t want a narrator, which would be this intrusive presence hanging over the film.

So he hit on this goofball idea to have Gonzo play Charles Dickens — and to make it even sillier, he had a sidekick, Rizzo the Rat, because obviously Charles Dickens should have a sidekick. And he delivered this prose that linked the episodes of the film together. It was the first time that Gonzo became soulful — and we kept each of these pieces as they unfolded, and now we can draw upon all of them, as part of our arsenal.

(Clip: Muppet Christmas Carol, Scrooge brings a Christmas turkey to the Cratchits, and Gonzo talks about Tiny Tim, “who did not die.”)

I think that’s my favorite film ever. I love that film.

Now, for the final part of the talk: becoming real.

When we create characters, they become like children to us; they have part of our DNA. But then our characters go out into the real world, and they make friends, and they’re affected by the world. And then sometimes they affect those friends. I’ll be at something like this, and someone will come up and express gratitude for something that I helped them with, saying, Gonzo taught me that it’s okay to be different. It’s rare to find work like this, that uses your strengths and your weaknesses.

I said in the beginning that I wasn’t like Geppetto. But my work with the Muppets led me along that path. After many years of making puppets, as I got older — like Geppetto, I got married, and I made a little boy and a little girl. And they weren’t like the puppet characters — you’d set them down, and they’d get up again. Like Geppetto, I got to be a real life dad. My wife and my daughter are here today, and they, along with my son, are the culmination of my work with the Muppets. And I couldn’t be happier.

So there’s another clip I want to show, from The Animal Show, which was a series about a talk show for animals. An animal would come on the show, and the hosts — a polar bear played by Steve Whitmire, and a skunk played by me, of course — they would interview an animal about his life. And then, like on a talk show, the animal would run a clip, but it was a film about how those animals live, rather than a movie it was plugging. By the end of the series, we were kind of running low on animals, so they decided, how about we use a human? So I appeared on The Animal Show as Dave the Human, with my family appearing in the clip.

So there’s another clip I want to show, from The Animal Show, which was a series about a talk show for animals. An animal would come on the show, and the hosts — a polar bear played by Steve Whitmire, and a skunk played by me, of course — they would interview an animal about his life. And then, like on a talk show, the animal would run a clip, but it was a film about how those animals live, rather than a movie it was plugging. By the end of the series, we were kind of running low on animals, so they decided, how about we use a human? So I appeared on The Animal Show as Dave the Human, with my family appearing in the clip.

(Clip: Dave the Human, on The Animal Show.)

And there’s one more thing to show, along the lines of puppets becoming real — this is one of my favorite bits of puppetry. This is Frank Oz as Marvin Suggs, and his Muppaphone.

(Clip: Marvin Suggs and the Muppaphone play “Witch Doctor”.)

I just never get tired of watching that.

(Then came the Q&A session, which went like this.)

Q: (A young boy says that he learned in school about a corona on Venus that looks like Miss Piggy.)

A: Okay. Wow. Really makes you wonder.

Q: The last time Gonzo was in San Francisco, he was looking for a party trick; I wonder if he ever found one.

A: I’m sorry, I don’t know what you’re talking about…

Q: It was from an old interview, from about twenty years ago.

A: Yeah, here’s a little secret — I don’t pay attention to myself. So I have no memory for things that I’ve said. Sorry.

Q: How did you meet Jim?

A: I was on a rare business trip for HP, which took me to Pennsylvania. Since I was on the East coast, I took a week’s vacation time, so I could go to New York and sleep on a friend’s floor, because I wanted to meet Jim. I’d spoken to Frank Oz at a puppetry festival, and I happened to know his real last name. When I got to New York, I called him — I hadn’t prepared at all — but his name was in the phone book. Jim wasn’t in town, but Frank arranged a visit to the Street.

I was on the Sesame Street set for a week, and I made friends with people there. I brought some puppets that I’d made, and showed them to Bonnie Erickson, one of the designers. She said, you’re good, you could easily work with us. But then the trip was over, and I went back home.

A month later, I’m at my desk at HP, and the phone rings. I pick it up: “Hi, this is Jim Henson.” I was so surprised and amazed, I jumped up — and I looked around at all these people working, and I’m thinking, I’m the only guy here talking to Jim Henson!

So I arranged to meet him when he was shooting in LA; they were filming an appearance on a Perry Como special. I got to their hotel on Saturday morning, and Jerry Nelson was there instead. He told me that Jim’s mother had died, and Jim was at her funeral. I said, I’ll go home, this is obviously a bad time, but Jerry said no, he’s coming back the next day, and he wants to meet you.

The next day, I went to the studio, and met Jim. We sat in the rehearsal room, and I showed him my design portfolio. First there were some tractors, and HP equipment, and then my first puppet, which was a mess, and my second puppet, which was starting to pull together, and my third, and my fourth… and he was so kind to me.

I apologized, I said, I feel uncomfortable, I know this is a bad time for you — and he said no, you came down, I wanted to meet you. He was so kind. They were just the nicest people. I brought out some puppets to show him, and he put one on, and we were ad-libbing together. I couldn’t believe it! I’m ad-libbing with Jim Henson! He’s using a puppet that I built!

There was just an incredible grace about him. He invited me to come back, and watch the shoot. His wife Jane sat next to me, and we watched them work, we were just enjoying it. And Jane leaned over, and said, so? Are you going to be working with us? I said that I didn’t know, I’d just met Jim, and she said, I’m sure Jim will find something for you to do. That was 1972.

Q: With the live concert at Outside Lands and a new live attraction at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World — is this a trend, toward live interactions?

Q: With the live concert at Outside Lands and a new live attraction at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World — is this a trend, toward live interactions?

I don’t know if it’s a trend. We’ve done it very rarely; it’s not our strength, and it’s hard to make it work. We usually want to be able to do shoots, and multi track. But Kyle Laughlin, who works with us at Disney Interactive, has a friend at Outside Lands, and they were asking if the Electric Mayhem band could appear.

I didn’t know if we could do it. Doing this — (putting his arm up, with his head on the side) — for five minutes, remembering the sax parts for five songs. Also, we didn’t know if anybody would like it — but the audience loved it. It worked!

They built these genius harnesses, that would attach at the waist, and they have a little cup to help you hold your arm up. And it was the strangest thing, to perform — we were singing live — and hear all this noise from the crowd. We don’t even know how to play our instruments!

Billboard Magazine ranked the top 10 bands at the festival, and #1 was Dr. Teeth and the Electric Mayhem! Rolling Stone wrote about the top five bands, and we were one of those, too. It’s really a surprise, because it could have gone very badly for us. it was a leap of faith.

Q: (Jamie Carroll identifies himself as a reporter for Tough Pigs…)

A: Oh, Tough Pigs, this is a fan website. They’re the greatest guys, they’ve been hanging in with us for many years.

Q: (Jamie asks if Dave has a favorite musical moment.)

A: Gosh, we’ve done so many… I can’t even remember them all. The focus on music came from Jim, it was an incredible focus for him. When we lost Jim, it receded a bit. We all miss it, we want to do more.

Q: When you’ve got two characters in the same scene, do you film them separately?

We can’t do more than one at a time, obviously, so we get trusted associates to fill in for the character. We do the close-ups, but for wide shots, somebody else does the character. Sometimes we have them throw the voice in and we record it later, or sometimes we pre-record the voice and play it live. It’s a matter of finesse, and having very good people to work with. That’s how we make it work.

Q: On that “Dancing With Myself” clip — how many people were involved?

Q: On that “Dancing With Myself” clip — how many people were involved?

It’s hard to remember — we had maybe four Gonzos, at the most six? Because they were out. Every ten years, they make two more. I can’t really remember how we did it; we used green screen. But it’s funny, I could look at it and recognize which Gonzo that Steve Whitmire was performing, because I recognize his puppetry style.

Q: (Debbie McClellan, who’s in the audience, prompts Dave.) I want you to tell the story about Gonzo at 25 years, and how he continues to evolve.

A: Okay, I’ll tell half that story, and then I’ll get someone to help me with the other half. We had a celebration of the 25th anniversary of The Muppet Show, a fan convention in California. We promoted that in New York on the Today show, with Kermit and Gonzo interviewed by Maria Shriver.

I needed an angle — we have writers who provide questions and answers, but I’d just arrived in New York, and I had to go to bed at 10:00 New York time, because they were going to pick us up at 4am. I’m just about to go to bed when an envelope is slipped under the door, with ten pages of Q & A. I thought, I’ll never be able to remember all this.

So I decide my angle is going to be plastic surgery. Here we are 25 years later — we look the same, but the audience is 25 years older! So Gonzo talks about getting work done, getting your nose lifted. I was just riffing on that, and Kermit had to talk about the details of the celebration.

At one point, I looked over at the monitor — and saw that Gonzo’s eye was messed up. One of the eyes was stuck open — all of a sudden — and it wouldn’t fix itself. A little prong got knocked out of place — I don’t know why after all those years it finally happened, on live television.

Maria noticed, and asked, Gonzo, what’s wrong with your eye? And Gonzo said, well, I’m going to have to get more work done! So when the puppet went back to the workshop, I asked, can you build that in?

(Then Dave pulls Gonzo out, and Gonzo sits on the lectern, ready to answer questions. Dave’s daughter gets up to perform Gonzo’s right hand.)

Gonzo: Let me just take over, okay? I mean, wouldn’t you rather have me explain it?

(Gonzo notices the audience member with the chicken hat.)

Gonzo: Can you please put the chicken hat on your head? I’m not comfortable with her sitting on your lap like that. (Laughs) Now I forget what I was going to say — I’m still looking at the chicken! Where was I?

Dave: Actually, I do forget what I was doing… this is the beauty of puppetry, you can do anything. You’re still laughing!

Gonzo: Oh, yeah, the eye mechanism. They built it in, so now I can go: hey, what? (He raises the brow on his right eye.) Seriously, I want to meet that chicken later. So, does anybody have any questions for me? (A moment of silence.) Oh-kay, thanks a lot…

Q: Some of the puppets have rods on their hands, some have live hands — how many people are involved, with the live hands puppet? Are there three people under there?

Gonzo: I don’t really take religious questions. I have no idea what you’re talking about. Maybe he can answer.

(Dave explains about rod hand puppets — there’s a rod attached to each hand.)

Gonzo: I don’t know what that thing is, I’ve never seen it before.

Dave: For puppets with live hands, usually the main puppeteer performs the head and the left hand, and another person does the right hand. Is it crowded? Yeah, these puppets are mostly smaller than we are. What’s it like under there, you don’t want to know. All I can says is you avoid garlic, and get a good antiperspirant.

Q: What’s your real relationship with Camila?

Q: What’s your real relationship with Camila?

Gonzo: The real one? I can’t get into that kind of thing. That’s a very personal interspecies thing.

Dave: I can answer that. (Dave addresses Gonzo.) You can’t hear me, you’re just a puppet. (Gonzo slumps down, like he’s hypnotized.)

Okay, while he’s away… I don’t think he can tell chickens apart. He’s just attracted to any chicken he sees. So it’s my personal feeling that he just finds a chicken, and calls it Camilla. Chickens aren’t that bright — if you call them Camilla, they’re Camilla, and then they go out on a date.

Q: Of all your adventures, which was your favorite?

Gonzo: My favorite adventure? Being here with you today. I’ve never seen anything like this!

Q: (A man starts talking in a Miss Piggy voice)

Gonzo: Security, we have a weirdo here!

Q: Who’s the most glamorous star you’ve ever worked with?

Gonzo: See, that’s tough — if I answer that, it would hurt the feelings of all the others! I worked with a lot of great people. We can meet up later, and I’ll tell you.

Q: (A woman says that she’s distantly related to Charles Dickens, and wants to thank Gonzo for representing her ancestor.)

Gonzo: Sure, any time. Does anyone else have an ancestor?

Q: What kind of animal are you?

Gonzo: I’m not certain. For a while I thought I was an alien? But then that might have just been a movie. I don’t really know… I’m a fraud. I’m a nothing.

(The audience says Awww…)

Gonzo: Okay, thanks. I’m good.

Q: Can you imitate Bunsen Honeydew?

Q: Can you imitate Bunsen Honeydew?

Gonzo: Me? I can try. I’ve never done this before, you know. (As Bunsen🙂 Guess what? I’m Dr. Bunsen Honeydew, wearing a Gonzo suit! Don’t tell anybody.

Q: How much rehearsal time did you get on The Muppet Show?

Dave: It varied, from zero to a tiny bit. We usually don’t rehearse. For Outside Lands, we did a couple of days, ran through the show six to eight times. On set, we just did blocking. You’d get on the floor, and start figuring where you’re going to stand. A lot gets worked out at that point. If there were special props, you’d have a special meeting about it.

Q: When you appeared live at the D23 convention, on the riverboat: how many puppeteers were working on that?

Dave: The way that the Muppets work, or the Muppet Show franchise, we have seven people — eight, now — who do the main characters. And then we have tiers of people in different cities that we can call on, to do different characters. So if we need to get puppeteers in LA, or others in New York, London, Toronto… we have colleagues in all these places. When we go there to work, we can call these folks. That was a great thing about Jim — he was very global, so we have colleagues around the world.

Q: When you started, you didn’t really have a singing voice — but by the time you worked on Fraggle Rock, you did a lot of singing. How did you get trained?

Dave: I’m not a singer. I’m a total fraud. I remember the first time Jim and I were in an elevator going to the recording studio, I was really nervous — I’d never even been in a recording studio before, and there were real musicians there! Jim said, oh, I love singing with a live band, it’s so much fun. And I’m going, homina homina… I’m still really an impostor.

I don’t even know what I would sound like if I had to sing in my own voice, but I can sort of pull it off in character. And as a complete impostor, that’s really been one of the things I feel the most lucky about. I mean, I was in a rock concert last week! I mean, hello? This is crazy!

Q: Where did you get your shirt?

Gonzo: I have a designer in New York. And another one, Stefan, who just did my entire wardrobe. I’ve got maybe thirty new shirts.

Dave: Okay, I guess that’s the last question we have time for.

Gonzo: I know, I know, I go back in the box…

Concluding thoughts by James Carroll:

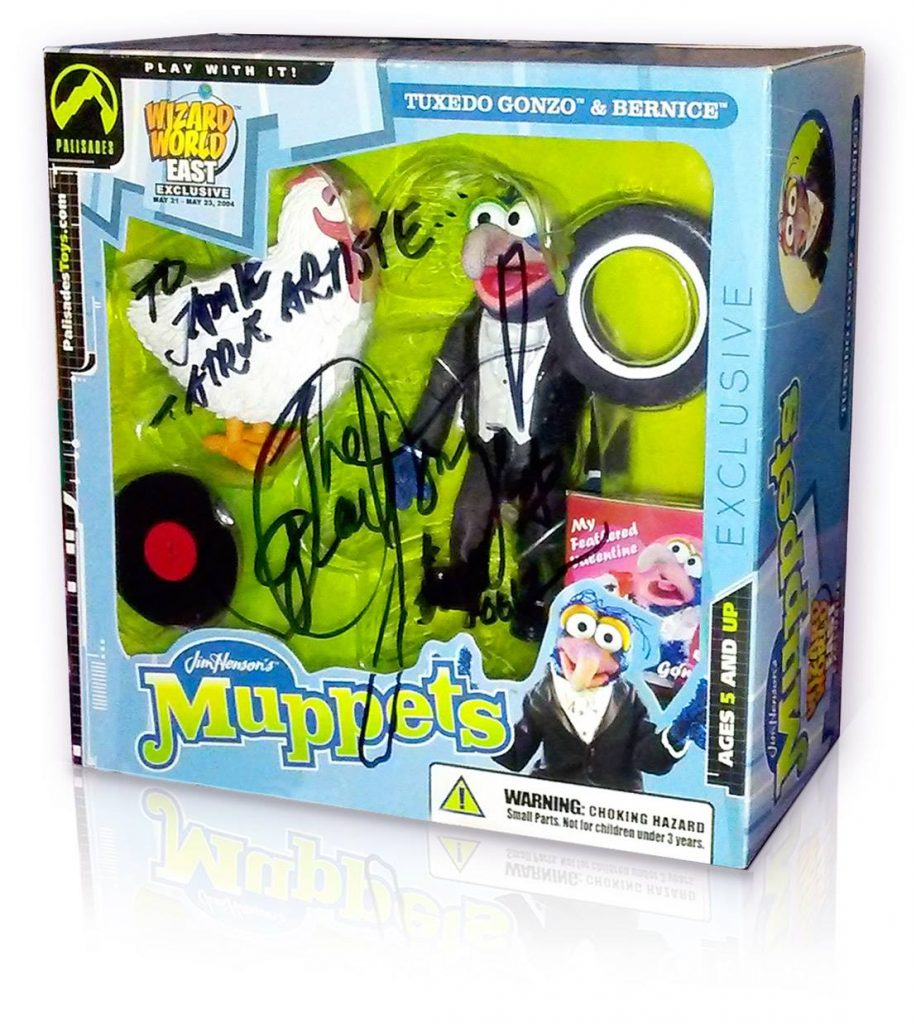

The work of Dave Goelz has always had a particular impact on me, so I jumped at the chance to help cover his sold-out show at San Francisco’s own Walt Disney Family Museum. His signature character not only told me it was okay to be a weird little guy, Gonzo also taught me to find great strength in that through the Wishing Song anthem on the Madeline Kahn episode of The Muppet Show. That was my “Bein’ Green” moment as a kid.

Among the memories and anecdotes, Goelz shared that the development of each of his characters comes from extracting and exaggerating his own flaws. That humanity, tempered with anarchy, is one of the most definitive Muppet characteristics and the reason why they’ve endured for decades. I’ve had the privilege of contributing some legit work to Muppet products over the years and finally had my most prized Palisades piece signed. Considering last week’s monumental Mayhem performance, it’s been a phenomenal week to be a Bay Area Muppet fanatic and I hope this is just the beginning of more.

Thanks again to Danny and James! Click here to sit down on a huge pile of garbage on the Tough Pigs forum!

by Danny Horn and James Carroll