You might not know Mark Saltzman’s name off the top of your head, but if you’re a Muppet fan, you’ve enjoyed his work. His credits include writing scripts and songs for Sesame Street, and writing for The Jim Henson Hour, The Muppet Show Live on Tour, and Muppet Magazine. Mr. Saltzman has some great memories and insights, and he shared so many of them with us that this will be a three-part article!

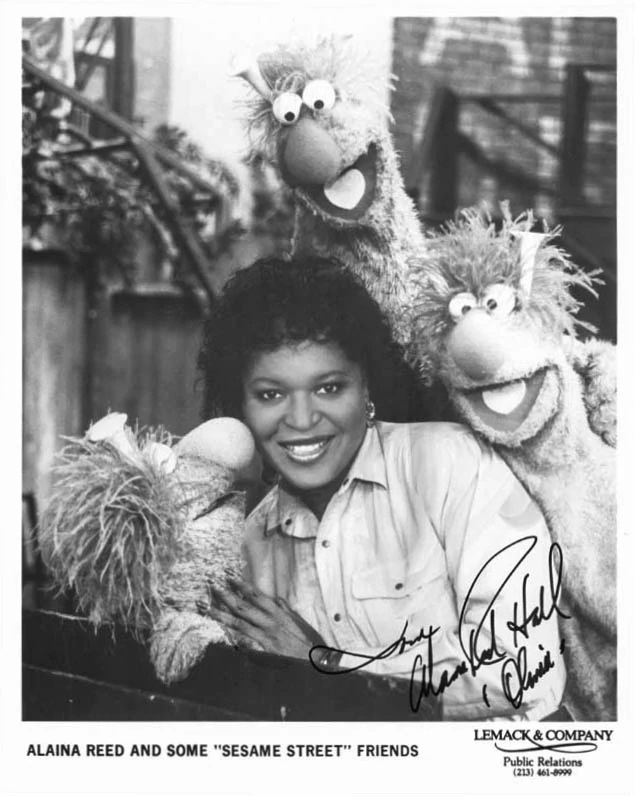

In this first installment, Mark talks about writing a magazine in Muppet voices, composing some all-time classic Sesame Street songs, creating Placido Flamingo, and the brilliance of his colleagues Alaina Reed and Joe Raposo.

[Note: This interview was conducted over the course of two conversations and has been edited for clarity.]

Tough Pigs: How did you first start writing for the Muppets? Did you start by working with the Sesame Street group first or the Muppet Show characters first?

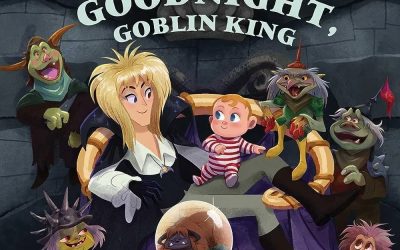

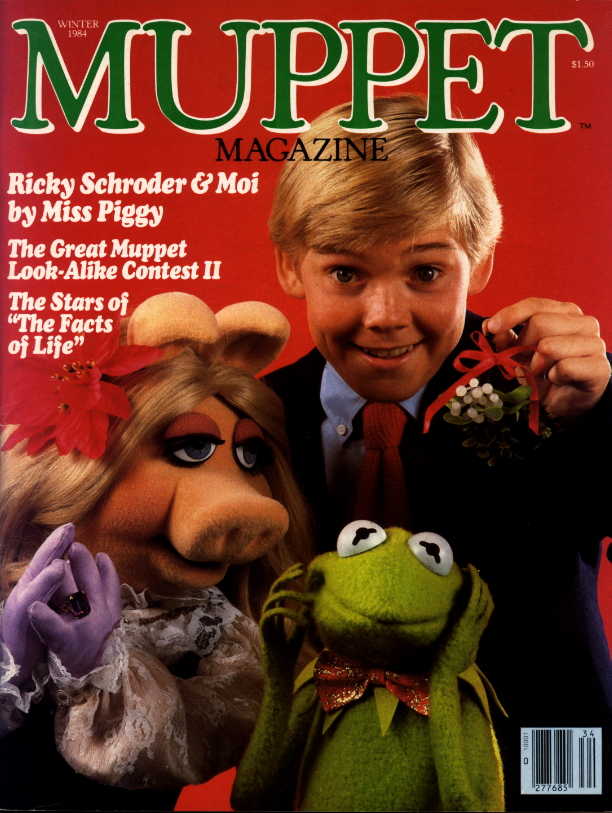

Mark Saltzman: The first thing I did with the Muppets was Muppet Magazine, which was around in the ‘80s. I think Lorimar Pictures was the publisher, and I’d been working in children’s magazines around that time, while I was also doing theater and cabaret songwriting. You know, the New York writer’s life.

I can’t remember what brought me to Muppet Magazine exactly, but that was the first place I got into the Muppet universe. We started the magazine, and little by little, I got noticed by the higher realms of Muppetry, and I was invited to start doing some TV things and videos. That’s what got me in.

TP: So they liked your work, obviously.

MS: They liked my work, yeah. And Muppet Magazine was connecting to the voices of the characters… I’m trying to think [which characters]. Miss Piggy I connected with, and some of the more oddball [Muppets] like Gonzo. I found it easy to write in those voices, and it turns out that was something that they really desired in their writers. You kind of had to be able to channel these characters and write in their idiosyncratic ways.

TP: It has to be an interesting magazine article, but also written as if Gonzo or Piggy wrote it.

MS: Yes, exactly. That was the notion of Muppet Magazine, that the Muppets were editing and publishing this magazine.

TP: Did you ever get any kind of pointers from the TV writers, or the performers, about what the characters should sound like? Or did they just kind of trust you to do it on your own?

MS: It wasn’t from the performers. They had a publishing division – they were doing Muppet books and things. It was Jane Leventhal. She was sort of the voice of the Muppets for us – Jane was kind of our editor within Muppets. I remember at one point there was something I wanted to do with music education and Muppets, and I was sort of telling Jane about that.

And she said, “Oh! You know, Jim [Henson] was thinking about this. He was just talking about that. Let’s go tell him.” It was so casual! I remember when I met him, my heart was thumping. How do I be cool about this? I was sort of breathless. I don’t get star-struck too often, but for this I had no preparation. I remember that pretty clearly.

TP: Yeah, to have that happen unexpectedly I’m sure would be life-changing.

MS: Well, I guess what was life-changing was “I’ll never have to be frightened of this again.” I can’t say “Oh, my life took a turn” or “My career took a turn.” It wasn’t that; it was more getting thrown in the deep end of the pool. And I stayed afloat, I got through it, I stayed in the pool. And lived to work more days with Jim.

TP: One thing I’ve always wondered about Muppet Magazine – you worked on some of the celebrity interviews?

MS: I did, yeah.

TP: Did you actually interview the celebrities and then kind of re-write it in the voice of the characters? How did that work?

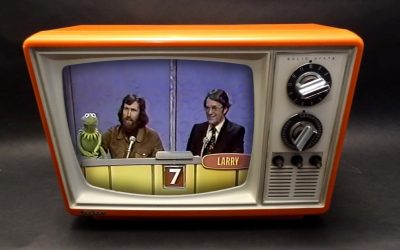

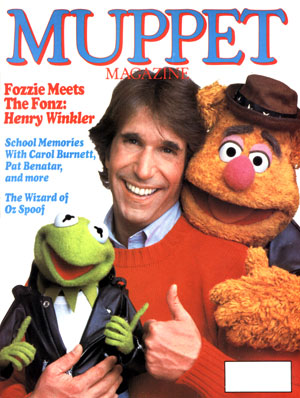

MS: That’s exactly how it was done, yeah. I remember doing Henry Winkler. You just did it like a regular interview. Everyone was sort of in on the gag, you know – you might say “Oh, I know Kermit would want to know…” or “Miss Piggy would be very interested… She has a big crush on you, she’s going to want to know what you wear in bed…” (Laughs)

I haven’t been asked this in forever, so I’m really pulling this out, but I remember the Henry Winkler one for some reason. He was a New Yorker from the Upper West Side, and very into Muppets and what we were doing. Generally, it was somebody smart like Winkler. They’re contributing, and it’s more like you’re writing a comedy sketch together. I just remember that being one I did, and how collaborative it was. He was just that kind of guy. There might have been others that… not that they had to be forced into it, but had to be a little more spoon-fed. But he was right on top of it. He got the joke.

TP: I’d like to think that he’s the kind of guy who would.

MS: He’d done a lot of comedy. The celebrity stuff was almost the easiest. It’s the flashiest. But you had to dig down and come up with ideas for stories to fill up this magazine every month.

I remember one thing that I did consistently was the section called “Mondo Muppet,” and it was supposedly edited by Gonzo, and it was kind of “weirdness in the world.” It could have been how to make some disgusting thing for Halloween that would look like mucous. Something like that, but all through Gonzo’s sensibility. It was a two-page or four-page spread.

And you are writing for kids, so maybe giving them weird recipes or Ripley’s Believe it or Not kind of stuff about the tiniest bat. I remember having a really good time writing that. That was fun.

TP: And eventually you ended up working for Sesame Street.

MS: Yeah, and it wasn’t as a result of that path, interestingly enough.

TP: Oh!

MS: There was kind of an invisible barrier between the Muppet Show Muppets and the Sesame Street Muppets, and they were kind of kept separate. These were the educational writers, and these were the more schticky sitcom writers, and there wasn’t a lot of overlap.

I started out on the Muppet side, and then in my theater musical hat, I worked on a revue called A My Name Is Alice, which was an ‘80s, feminist-oriented show, all women in the cast. It was a surprise hit, and ran for years, and there are still productions out there now.

One of the members of the cast was Alaina Reed, who played Olivia on Sesame Street. She was a major New York performer at the time. She had a legendary nightclub cabaret act. There weren’t a lot of black women doing that, and she almost had that to herself. A very elegant but slightly raunchy cabaret act – Bette Midler was doing that. So she was a known New York commodity when the show was put together. She was already on Sesame Street, and she was moonlighting in this show, and was pretty much the prevailing personality of A My Name Is Alice.

I loved writing for her. I met her on this, and we just sort of connected. I wrote her a blues singer parody – I wrote right to what I knew she did, and she was strong at. We just loved working together. We’d sneak away, which is not the way it’s supposed to work in theater. The director is the king or queen. But we’d slip out, and go to a studio and work on material together, and it was just one of these connections. When the show was done and running, she basically threw me in a gunny sack and took me up to Sesame Street and said, “He’s writing for me.” (Laughs)

TP: Wow!

MS: Nobody said no to Alaina. It was basically “I found this guy downtown…” I still had to go through all these auditions. I went through the trial and all that. But yeah, I liked writing songs for Alaina – a lot of them are on YouTube now.

TP: I’m not familiar with her cabaret act, but I always thought she should have been a bigger star just based on her screen presence and her singing talent.

MS: Well, she came out to LA and she was on a sitcom, 227. When she’d come back, her standard punchline was “Well, I thought I’d get to do something on camera besides standing on a stoop –“

TP: The set of 227 is a very similar stoop!

MS: Yeah. But she opted for coming out here, and she did really well as far as advancing herself with the sitcom. That was a major series, and she was a regular every week. I think maybe if she had stayed in New York and opted for Broadway shows and things, she would have had that too. She died pretty young.

One of the things we were working on in between her TV stuff was her one-woman show about her life. She was brought up by her grandmother. She had sort of a wild mother. Her grandmother didn’t approve of Alaina’s mother bringing her up, so she sort of grabbed this girl and was very strict. Then Alaina showed this talent, really early, like in middle school talent shows, and Grandma wasn’t sure about it. (Laughs) It was sort of a crisis of whether this means another wild woman in the family if she let the show business thing happen.

But Alaina was very practical. She knew the way the wheels turned in the business. She was terrific. I’m so grateful to her, as far as the entire Muppet experience.

TP: What are some of your Sesame Street scripts that you’re most proud of?

MS: Oh boy.

TP: Or maybe most memorable?

MS: I’m really proud of the songs, because to this day some of the songs survive. The scripts kind of come and go, but still I’ll look on YouTube and some kids’dance troupe is doing “Caribbean Amphibian.” I have a Google alert for “Caribbean Amphibian,” and one time two girls at the New York State Forestry School were singing iton ukuleles. I knew a young cousin of mine was at that school, and I said, “You have to track down these girls and tell them we’re related!” Of course, he knew them. This was, I’d say, a year ago, so this song has legs! They’re frog legs, but yeah.

That kind of thing gives me a lot of pride. And some of the international stuff that they put me on. I think of all the writers on Sesame Street, I was one of the few who knew a little bit of Hebrew, from having a bar mitzvah. I could read it. They were getting Israeli Sesame Street together, and they sent me over there a few times. That was a great experience. I’d never been that far away from home before. I’ve been back several times.

Hoots the Owl had a jazz club – a minor, minor character, but it was jazz. There was a song, “Birdland,” that was his nightclub, and Alaina was a singer there. I remember writing “It only happens at Birdland” for her, and that felt like doing her cabaret act again. Hardly any educational value.

It always made the Sesame Street scripts so hard, because they had to be funny sketches, and there had to be something taught. I’m sure you’ve heard this from people, the curriculum goals. They were very strict about this. I mean, that’s what Sesame Street was. They had a right to be strict. Also, the humor had to be adult and preschool at the same time. It was adult sketch, preschool-accessible, curriculum goal, and funny. That’s four layers!

TP: Yeah!

MS: Meanwhile, our brethren over at Saturday Night Live were one layer! (Laughs) We were the TV sketch-writing talent in New York, and you know, they’re getting paid five times as much.

TP: Not like public television money.

MS: Yeah, it was network! And I’ll tell you, for anything – writing Hollywood movies, anything – nothing was harder than this. I think we all knew it. Once you get one thing right, then it’s like “Oh, how do you get the curriculum into it?” Then “Oh, I got the curriculum in, but it’s so boring!”

There were some kind of easy-peasy curriculum like learning social skills and things like that. “Caribbean Amphibian” was geography, I remember that. That was the curriculum, and the mention of Haiti and Puerto Rico in the song were enough to carry that. And there was an animated map. Well, it wasn’t really geographically correct, but it was enough that the kids would hear about these places, and that they were in the Caribbean.

TP: So that qualifies. So in a case like that, did you come up with the song first, and then you’d have to explain what the curriculum was, or did they say “Write a song about geography” and that’s what you came up with?

MS: At the beginning of each season – what I call a “semester,” because that’s how educational it was – they would give us a curriculum guide. Some of it was carved in rock – the letters of the alphabet, and the numbers. But some things would change from year to year. There’d be new stuff, and the softer stuff would kind of come and go. “This year, we’re doing an emphasis on Spanish language and culture.” That was a great one. Maybe it was “This year, it’s going to be about disabled kids.”

There was one year I remember it was going to be music, and you never knew how touchy and volatile music education is until these people came in for a meeting with the writers. You really cannot have the Suzuki people and the non-Suzuki people in the same room. It couldget ugly. It couldcome to blows. But that was a good one for me, music education, because I taught music in my time, so that one wasn’t bad.

But the notion that, to work hard enough to write a funny sketch and somehow bend itself around to a curriculum, was kind of tough. That was part of the tension — when your sketch, right at the top, had to say “TITLE OF SKETCH,” and then right under it, “CURRICULUM GOAL.” You had to have something from the curriculum guide right there.

TP: Do you remember anything you wrote that got rejected because it didn’t fit the curriculum goal, or for any other reason?

MS: Hmm… I am one who remembers my rejections. (Laughs) But I have trouble recollecting this, because generally if Norman Stiles, the head writer, liked the sketch, you would dig into the curriculum and say “Okay, how can we get this past the educational division?” Sometimes you’d be brainstorming, “Oh, this would be a funny thing for Bert and Ernie!” and then the head writer might go to the other writers and say “You can make that ‘getting into social groups.’” Which is a valid goal, to show kids that if you see some other kids playing, here are some strategies to get into the group, which is high tension and anxiety for some kids.

TP: I remember a few segments about that kind of thing.

MS: Yeah. Those kinds of things could save the day. There was a thing called “word recognition” that was really interesting, just the way some kids learn, that you’ll recognize the word “STOP” before you’re literate. Before you know that’s an S and that’s a T. You see it in the car, and Mom and Dad say “That’s a stop sign.” You don’t even know those are individual letters, you just know that word means “stop.” It’s just one way kids learn. There’s was the Harvard School of Educationoverseeing all of this, and they discover things, and we try to get that on Sesame Street.

There was one song I wrote with Joe Raposo called “New Way to Walk,” and that came out of looking over the list of words that we should teach kids to recognize. “Walk” was one of them, so that led to the traffic sign that would say “WALK,” and that was sort of the essence of the curriculum. As long as the word “WALK” kept flashing on the screen, we were fine with education, and it was sort of rock video-ish, so repeating that was nothing. It was just part of the visual vocabulary. It was first done by the Oinker Sisters.

TP: Was that your idea, to have it done by a group of pigs called the Oinker Sisters?

MS: Yeah, I’ll take the hit on that one. (Laughs)

TP: It’s a good one!

MS: A few seasons later Destiny’s Child was on, and this rarely happens that you do another recording of the same song, but I think they liked that song. And they were like the Pointer Sisters at that point.

TP: Did you get to be there on the day when Destiny’s Child recorded that?

MS: Yeah. You can see it on YouTube. It doesn’t get more pop than Destiny’s Child – and the curriculum held, the kids learned to read the word “WALK,” and I got Beyoncé on my résumé!

TP: That’s pretty good! I don’t actually remember where I read this, but you’re credited with creating Placido Flamingo. Is that correct?

MS: Yeah, I think I was one of the few opera lovers at Sesame Street, and the office is right across from the Metropolitan Opera, so I’d be dashing out from a meeting to catch a matinee. I think that just came from the pun –Domingo sounds like “Flamingo.” Then I had all those opera parodies at my fingertips. That might have been [built] around the music curriculum, because whenever he came in, he did opera, and opera style. That was curriculum enough.

TP: It’s teaching kids culture.

MS: Yeah, but that would be a touchy concept. Whose culture is it? The idea is that the child should be exposed to all types of music, and there’s a type of music in the world called opera – I think that would have applied. I remember one opera parody I did for him, which was about opposites. It was a parody of “Rigoletto.” The subject was opposites, and that’s a hardcore curriculum. I had to get a real curriculum in when Placido was singing. And that was the late Richard Hunt!

TP: Yeah, I’ve heard he was a big opera fan too. Did you have him in mind for the character when you first wrote it?

MS: I didn’t. The puppeteers weren’t quite that present, because they’d be off at this point doing Muppet movies. I don’t think I ever really knew the strengths of each of them. You kind of knew not to write new characters for Frank and Jim. They were busy guys, so it was always going to be the second tier.

When you say Richard was the opera guy… They all could have fake-sung opera, you know? They had that kind of talent. And even right now I’m thinking, how did that happen? You’d have a character and this puppeteer would be there, or that puppeteer. It seems mysterious!

TP: I guess he was just in the right place at the right time!

MS: I think it would be who’s available, and we’re shooting it that day, and there’d be some sort of woodshedding with the characters with different puppeteers, just trying it out. With Placido, there was this very extreme design, so who could manipulate that? It may have down to Richard having the manual dexterity to move around that big beak. Then there was the day when the other Placido came onto Sesame Street and actually sang with him. That was exciting.

TP: Right, that must have been thrilling for all of you.

MS: Yeah. I wasn’t sure he got it. Opera singers are strange creatures. I couldn’t tell if he was indulging this – on some level, it was a tiny bit insulting – or if he was really enjoying himself. It’s tough to tell with performers. But I had a good time.

TP: I wanted to ask you about a couple of your other songs that you either wrote or co-wrote. “Down Below the Street,” which is an a cappella song.

MS: Yeah, that was fun! You can see the curriculum is just right out front there.

TP: “What’s underground in the city?”

MS: Yeah, and it was really specific. It was like “What’s in a building?” or something like that. These things were all in academic language, which is sort of the enemy of dramatic writing. I can’t think of exactly where that sat in the curriculum, but they did a really great animation for it. And I didn’t know that stuff going in – the layers going down.

There’s also always something from the conception of Sesame Street where you want to skew toward certain viewers. TV was pretty white and suburban, and from the get-go Sesame Street was going to be urban, black and brown, so these kids would have representation. However the academics phrased it, whenever you were dealing with urban environments you were on safe ground.

TP: You wrote one called “Transylvania 1-2-3-4-5.”

MS: Yeah. Was Alaina in that?

TP: I don’t have it in front of me, but I think it’s another Birdland song.

MS: I think she looks fabulous in it. I think she’s got a gardenia in her hair like Billie Holiday. [Editor’s note: Alaina Reed’s Olivia sang the song called “Birdland” at Birdland with a flower in her hair. “Transylvania 1-2-3-4-5” was sung at Birdland by Lillias White as Lillian.] That was the jazz club one, and that was a parody of the ‘40s song “Pennsylvania 6-500.” The composer’s name was Stephen Lawrence, and he was one of the ones I was paired with, along with Raposo and Sarah Durkee.

Raposo — you look back now, and he’s one of the great American songbook guys.

TP: Definitely, yeah.

MS: “Bein’ Green” is still so sophisticated, the songwriting in that. Forget about preschoolers. It’s a jazz song. It really feels improvised. It’s like “Stardust;” you don’t know where it’s going. Somehow it holds together. Joe was really seriously musically educated at Harvard and in Paris, and it happened that this was where he landed. He could have easily been writing string quartets. Sinatra liked his stuff a lot and recorded a few of them. Again, a guy who died so early. There was so much more for him to do.

I feel like if Joe had lived, we would have done a lot more together. He was extremely encouraging and flattering to me in our songwriting. Getting that from him was pretty special. He really wanted a Broadway show, and he tried one, Raggedy Ann. It got shot down. That was the first one, but he had more ideas, and in my imagination I would be writing these with him. And there he went, in his early fifties, and I felt like that part of his career was just getting started and he would have figured it out.

You’ve seen Avenue Q, right?

TP: Yes.

MS: I remember sitting down at a really early version in New York – somebody had told me, “You have to go see it. Don’t read anything about it! Just go see it. You’re going to love it.” Which I did. I knew there were puppets involved, but that was about it. I sat down I heard the first six chords, and they were Joe’s chords. You know, you can’t copyright a chord, but – Joe’s huge creative leap was, if you think of children’s TV music pre-Joe, it was toy pianos and flutes, really cutesy, Kukla, Fran, and Ollie, Captain Kangaroo. Music box music. That’s what children’s music was.

And in comes Joe with the Sesame Street band, and it’s a blues harmonica, it’s funk. And here comes “Bein’ Green” and it’s 52nd Street jazz and it sounds like improv. And this is children’s music now. The whole game changed, and that was Joe’s vision. I thought Avenue Q was a show he would have written. It’s a parody, and Joe had no shortage of ego, but he would have thought, “It’s me. It’s my sound. I gave it to Sesame Street so I’ll give it to a parody of Sesame Street.”

And more power to them – it’s a great composer, Robert Lopez,that wrote that score. But it was sad and it was touching that this was in the Raposo tradition and he wasn’t here to do it but it was still getting done. I was the only one who sat in Avenue Q and had tears in his eyes.

TP: He definitely established a very specific sound where you think “Sesame Street” as soon as you hear it.

MS: Yeah, and you know that’s not Captain Kangaroo. This is something urban, swinging, complex, and he doesn’t get enough credit.

TP: And a lot of people who love his songs don’t even know his name.

MS: I consider myself a sort of keeper of the flame when I talk about these things, so I like to bring Joe into it. Something like “Caribbean Amphibian,” that’s very close to reggae, and that’s maybe a little edgy for children. (Laughs) But it didn’t matter. You could go to all these different musics and it was the overall Sesame Street sound.

TP: One other song I wanted to ask you about: You co-wrote “Oh, How I Miss My X,” which I think is not only one of the best Sesame Street songs, it’s just a really great song by itself.

MS: Yeah! That was Stephen Lawrence. He was my songwriting partner on A My Name Is Alice, that show with Alaina, and I think he was already at Sesame Street. “Oh, How I Miss My X” was one where it was “Curriculum? No problem! The letter X.” And I think we knew Patti LaBelle was going to be on, and I really wanted to write something for her.

When you’re writing television, or screenwriting, you’re describing the pictures that are going to be on the screen. In sitcom writing, you’re kind of in that living room – you just sort of write the interchanges and the director will figure it out. But that’s probably where I learned screenwriting chops, doing things like that, because you really had to call for each shot: Patti’s in a boat, the X is in front, next shot. Patti’s back in the club, the X is at the table. Those kinds of specific visuals are the kind of TV writing that’s unique to Sesame Street.

Yeah, I remember that being a great day. Patti LaBelle’s in the studio!

TP: It must have been exciting to hear her sing your words.

MS: She gave it everything! These people would come on and they wouldn’t be condescending to the children’s show. She just planted her feet and wailed. People loved the show, and they still do, and they’ll come through, work for scale, and give it everything.

Stay tuned for part two, in which Mark talks about The Jim Henson Hour and The Muppet Show Live on Tour! Click here to fake-sing opera on the Tough Pigs forum!

by Ryan Roe – Ryan@ToughPigs.com