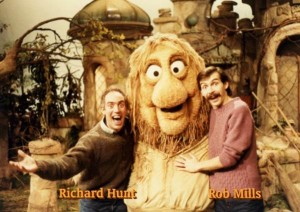

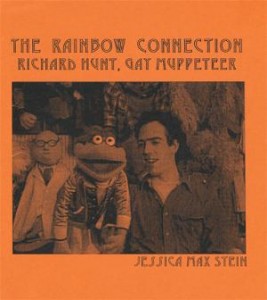

ToughPigs’ own Jessica Max Stein recently completed her zine entitled “The Rainbow Connection: Richard Hunt, Gay Muppeteer”, which takes a closer look at Richard’s life and legacy as both a performer and gay man. She had the amazing opportunity to interview Richard Hunt’s mother, Jane Hunt, and her partner, Arthur Miller (no, not the Arthur Miller) in Richard’s childhood home.

ToughPigs’ own Jessica Max Stein recently completed her zine entitled “The Rainbow Connection: Richard Hunt, Gay Muppeteer”, which takes a closer look at Richard’s life and legacy as both a performer and gay man. She had the amazing opportunity to interview Richard Hunt’s mother, Jane Hunt, and her partner, Arthur Miller (no, not the Arthur Miller) in Richard’s childhood home.

The following interview contains excerpts from the interview. To read the full version of the interview, visit her website at JessicaMaxStein.com.

Jessica Max Stein: What was Richard like as a kid? It sounds like he was a born performer.

Jane Hunt: When he was about four, he’d managed to fall and knock out one or both of his front teeth, so he had a hard time talking for a while. His godmother brought him this little outfit: little corduroy pants, a little corduroy jacket, sort of like an Eisenhower jacket, and a newsboy cap, like a man on the golf range. And he came out, and he stood there leaning on his umbrella, and he said, “I’m wearing my golfing outfit.” Out of nowhere. That was adorable.

He and his brother and sisters put on performances on the landing, and they loved doing that.

When he was growing up he did all kinds of things as a Boy Scout. He took his puppets to the Boy Scouts. For many years, every year we’d have a Memorial Day picnic out in the backyard here, with people from all over [at which Richard performed].

When Richard was about 5 or 6, we were at Howdy Doody. [Richard’s sister] Kate had been chosen from the crowd of children to sit up in the peanut gallery. Richard was sitting in that audience as well, and all us parents were taken back into a little viewing studio, to watch this live show go on. It was live then, nobody had taped shows. The host, Bob Smith, was getting up and guiding them to the end of the show. Richard came down to center, tugged on Bob Smith’s coat and said, “I’m a magician, and I want to do a ‘rick.” He had no teeth in the front, from his fall. “I want to do a magic ‘rick.'” And Bob Smith said, “Well, I don’t think we have time.” But Richard took it right out of his pocket, and he started doing the trick. I was sitting there with all these parents, like, ‘Oh my God. Oh my God.’ He’s doing this trick, something with balls, and he says — he didn’t say voila, what else do they say? Something very cute. And he completed the trick just as it went to black.

Arthur Miller: He had no fear. That is very true about him.

JH: Yup, no self-consciousness about asking if he can do something or another, which I think is so great.

JMS: What were things like for Richard as a teenager? You told a story about the kids teasing Richard when he was in middle school, following him on his paper route and dropping his papers in the mud.

JH: Yeah. They tortured him. He’d never told me. I never knew anything about it until the principal told me. His office was in a corner room in the school building right across the street, which was part of Richard’s paper route, and he saw it, day after day after day. I never heard a word from Richard about it. He just shrugged it off. “They’re jerks.” He certainly didn’t let it stop him from anything.

JMS: Richard not only was a born performer, he was a born upstager.

AM: Richard had a secondary lead in a high school production of “How to Succeed in Business [Without Really Trying]”. The main character sings a song in the men’s room, with the chorus.

JH: [Singing] “I believe in you, I believe in you.” They’re all in front of the mirrors and they’re doing their hair, straightening their ties and stuff. All of a sudden we see Richard has pulled out of his pocket a razor, and a spray can of shaving cream. He’s singing right along. He shaved himself. He then put cologne all over himself, and the place was falling apart. The other kids were washing their hands, not knowing what the hell was going on.

JH: [Singing] “I believe in you, I believe in you.” They’re all in front of the mirrors and they’re doing their hair, straightening their ties and stuff. All of a sudden we see Richard has pulled out of his pocket a razor, and a spray can of shaving cream. He’s singing right along. He shaved himself. He then put cologne all over himself, and the place was falling apart. The other kids were washing their hands, not knowing what the hell was going on.

AM: One gets the feeling this was not something the director had encouraged him to do.

JMS: He did that a lot.

AM: Yes, he did that a lot, and he got away with it. Most guys cannot get away with that stuff, because it’s a real no-no, it’s arrogant. Upstaging, you know?

JMS: They loved it at the Muppets. There’s some footage from the Fraggle Rock wrap party, where Karen Prell is giving a comic speech about what it’s like to be a Muppeteer, and she says, “The first rule of Muppeteering: If it moves, upstage it!”

AM: But the fact that he got away with it — almost always.

JMS: Because it’s funny!

AM: That’s a big part of it, but there’s something beyond that, I think.

JH: It’s as though everybody felt he was entitled to do whatever he wanted to do.

AM: Exactly. You give it to him. You say, “What the hell, it’s so wild to watch.”

JH: He would have spent hours with anybody in the cast, anywhere, helping them get through and do their parts and making suggestions to them. They’re not supposed to do that, but in high school I know he did.

JMS: He did it later; Kevin Clash talks about that, David Rudman talks about that.

AM: All of that stuff was in place way before he even heard of the Muppets.

JH: Yes, definitely.

AM: I can tell from these stories that — like you say, he was funny, and it was done in a generous spirit. Even though it was upstaging, there was a generosity to it.

AM: I can tell from these stories that — like you say, he was funny, and it was done in a generous spirit. Even though it was upstaging, there was a generosity to it.

JH: I think he would have loved it if they’d all started to shave, or something.

AM: You told me he took out Q-Tips.

JH: Oh yes. Cleaning his ears. [group laughter] Oh God, isn’t that too much.

JMS: Tell me about Richard cold-calling the Muppets.

JH: Yeah, from a pay phone. Right there on 10th and 57th. “Hello, I’m a puppeteer, can you use me?” “Well, we happen to be having a little thing going on right now. Why don’t you come on over and audition?”

JMS: That takes guts.

JH: It takes a kind of unselfconscious feeling about how you’re worth doing that. That you’re worth it.

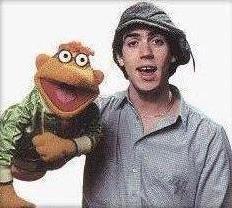

JMS: He’s like Scooter on The Muppet Show. They couldn’t do it without him. He meets the guest star, he’s everywhere, but he’s still always this little tagalong. Scooter in the Muppet Movie, he’s the road manager because he’s the one with the van. You get the feeling that he’s a little younger, a little “Hey, wait for me.” But at the same time, he’s in. He’s part of it, he’s it! Although I don’t know how much I’m extrapolating from the plot of the show to what happened behind the scenes.

AM: Scooter was to some degree based on Richard. I think they did that with a lot of the characters, just from what I see and what I’ve heard and what Jerry [Nelson]’s talked about, that they would take the essence of the puppeteer. I think they did it unconsciously, so that there was a lot of Richard in Scooter.

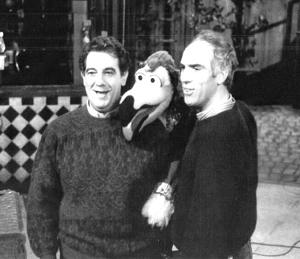

JMS: Richard seemed to have a wonderful camaraderie with Jerry Nelson.

AM: Jerry was almost like a father figure. Certainly like a big brother that Richard never had. Jerry was as gifted as Richard, as soulful as Richard. I remember I once said to him, “You guys were like the Abbott and Costello for this age.”

JMS: So many of their characters. The Two-Headed Monster. Biff and Sully.

AM: They ad-libbed their asses off on that show.

JH: They really intuited all that stuff.

JMS: Another great one is Placido Flamingo.

JMS: Another great one is Placido Flamingo.

JH: “Oh, Ree-chard!” One day I was walking home, past the Met, and going into the Met was Placido Domingo. I thought, “Richard would do this,” and I just walked right up, and I said, “Mr. Domingo, I’m sorry to bother you, but I wanted you to know that I’m Richard Hunt’s mother.” And he said, “Oh, Ree-chard! Hello! I am so sorry.”

JMS: One thing I like about what I’ve learned about Richard is his sense of abundance. It’s really easy to think that things are scarce, that love is scarce, money is scarce, and the stories that I see about Richard show that he really lived with abundance.

JH: That’s a very good word.

AM: Everyone tells these stories about Richard’s, what I call pathological generosity, almost crazy generosity. Once he hit it big, he wasn’t married, he didn’t have any children, he was never big with clothes and stuff, he just bestowed it.

He would take the family on these big junkets, these Hunt junkets. He took us all to Hawaii. The Hunt family was not just the brothers and sisters. There was a second ring of people who are as good as brothers and sisters. So he took between 15 and 20 of us to Maui, for a week, at one of the fancy-schmanciest, goyishe places. All white belt, white shoes, and into this milieu comes the Hunts, who change into their bathing suits in the parking lot, you know.

I would watch Richard working the planes when we would travel. He’d find any kids on the plane and he would approach them. Of course, at first the parents would have no idea who he was, he wouldn’t be working a Muppet or anything. And I would watch. You know the way people first are, “Who is this?” And then they do that turn, that shift, without even realizing it, they’re drawn right in. And then they’re watching their child dig Richard.

One of the things I always heard him say that would knock people out, to a little kid, is he would look at him and say, “You’re sick.” The kid would laugh at some joke or say something that a kid would say, some disgusting little thing, and Richard would look at him and say, “You’re sick.” And the kid would just love it.

I think he must have given something to more people than you could possibly imagine. Especially kids, who are so used to being condescended to or dismissed or pushed around or “Say thank you to the nice man,” all that stuff, and he would have none of that.

JMS: When did Richard come out to the family?

JH: Well, the first thing I knew anything about it was after that thing that you described of the time when [Kate and Richard] went waterplaning and crashed on the parkway, when Richard told Kate [that he was HIV-positive, around 1987]. She didn’t come running around telling everybody.

AM: He never really came out.

AM: He never really came out.

JH: No, he didn’t really come out.

AM: It was obvious, it was made clear, but he didn’t announce it.

JH: He kept things very separated, and in their places, where they belonged. Once he brought a group of guys to my house one night, I knew all these guys were gay. Did I know that Richard was at the time? I’m not really sure.

AM: I have a feeling there was a period in your family when everybody sort of knew. He would start to show up with guys, right?

JH: Yup.

AM: And nobody really said anything, you used to say to me.

JH: No, no. We welcomed them all the same, whoever it was, come on in. There was one boy who used to come over — he must have gotten out early from school, or he cut class or something, and he would come over here, and he’d sit on the floor with his back against the couch, and just wait for Richard to come home. And sometimes Richard wouldn’t come home, and so he would get up and say, “Well, I’m gonna go now.” That was all that was ever said.

JMS: You tell a story of a lover who predeceased him, who died in his arms. Do you remember who he was?

AM: The guy that Richard was with at the end, I forget his name, and I’m embarrassed. They lived together. And when he died — this was a guy who sat in a room, he was gorgeous, but he barely spoke. Richard threw a memorial for this guy, it predated the Henson memorial, in St. John the Divine.

JH: In one of those off to the side chapels.

AM: He threw this memorial with a gospel choir, and a string quartet. This guy was very quiet. Most of them were very quiet, sat quietly. Richard ran the show. Richard drew everybody around, and most of the guys he was with, from the time I knew him, were quiet, not overt. The last one hardly spoke at all. I never really saw him with a guy who was — like Richard, for example. Expansive.

JH: Richard was so unabashed, everybody knew, that I think lots of his partners weren’t used to the kind of openness they found in our family and in our family’s crowd. Certainly the guys in the Muppets, the guys at Sesame Street, were not in any way concerned about any of this.

JMS: I love the story that you tell about Frank Oz being at his bedside in his dying days. People ask me if he was out at the Muppets, if they were okay with it, and I just say, “Frank Oz was at his bedside when he was dying, and if that doesn’t tell you that they were okay with it, nothing will.”

JMS: I love the story that you tell about Frank Oz being at his bedside in his dying days. People ask me if he was out at the Muppets, if they were okay with it, and I just say, “Frank Oz was at his bedside when he was dying, and if that doesn’t tell you that they were okay with it, nothing will.”

I was curious about what Richard was like spiritually. I know he grew up going to the Episcopal Church.

JH: Yeah.

JMS: And then I know that Richard and David Rudman went to Macchu Picchu, and Rudman says that was like a spiritual pilgrimage. I know it’s a fine line. Maybe his art and his work and his life, living in the moment and all that, that is a kind of spirituality, but I was curious if he was ever more explicit about it.

JH: No, not in the sense of going to church every Sunday or anything of that nature. But I think he was spiritual. We’re the kinds of people who would be driving along in the car and say, “Look at that!” That kind of thing, that’s what we were all about. Everything new. When we were on Maui it was simply gorgeous. We appreciated every single bit of it. The whole family is like that.

AM: You know, I was just thinking, we were talking about Richard coming out. I think that was his spirituality. I think he kept that sort of to himself.

JH: Very private.

AM: You’d have to extrapolate it.

JH: I think many of these little deeds I love to talk about [exemplify his spirituality]. He was on Central Park West, and there were two old ladies with suitcases out on the curb, waiting, trying to get a cab and the cabs wouldn’t stop. So he had to walk over and say to them, “What is happening here?” “We need to get to the airport and the cabs won’t stop.” So up went Richard’s hand, he stopped a cab, said “Get in,” opened the door for them, got them in, “Tell them where you’re going,” and in the meantime he put the bags in the trunk of the car, gave the guy probably forty dollars or something, and sent them on their way. Now to me that’s spiritual.

The woman who was crying her eyes out because she wanted to kill herself, down there by the pond in Demarest. He noticed this woman crying, in the car, when he drove by. He stopped his car, got out, went back and said, “What’s the matter?” “I want to die, I want to die.” He said, “Just a moment,” and with that he hailed another car, said, “Please call the police right now, we need this woman to be taken care of,” and he stayed there with her and talked with her until the police came and took her off to the hospital. I think he thought, “That’s what I’m here for.”

This is a story you’ll love. There was a hurricane coming, up on Cape Cod. Everybody was asked to leave their cottages and go to the high school.

AM: Higher ground, to get away from the water. The cottages, the dunes, were right on the water.

JH: Richard had not been feeling well. Our friends Mary and Sonny were up there. They were seeing to it that he was fed and his sheets were clean and stuff like that. This is just before he died. I don’t think he even went back to the Cape after that time.

JH: Richard had not been feeling well. Our friends Mary and Sonny were up there. They were seeing to it that he was fed and his sheets were clean and stuff like that. This is just before he died. I don’t think he even went back to the Cape after that time.

Anyway, Richard did not want to evacuate. He said to Mary and Sonny, “Go on. You just go ahead and go about your business. I’ll be fine.” Well, didn’t he go and climb out his bedroom window, and sit on the porch roof, looking out over Cape Cod Bay, with the pilgrim monument down there in P-Town, and he sat up there during that storm hugging his knees, watching the storm come in.

There’s the spirituality for you. To be sure.

JMS: What was Richard’s memorial like?

JH: Richard had a funeral at St. John the Divine. It was just unbelievable. There were just as many people at his who were at Jim Henson’s. The place was jammed. It was amazing. Fred Newman got up and told the story of the time that he and Richard went to the Plaza for lunch. Fred said, “I had it in my head all along that he was not going to pay.” So he called for the check, and the guy puts it down, and he reaches to grab it, and Richard grabs him back. They’re struggling, fighting over this check. They absolutely got out of their chairs, and were on the floor! The maitre d’ came over and said, “Gentlemen, is there a problem?” That just brought the house down at St. John the Divine.

[The family home in New Jersey] is where the peonies bloomed every year. He grew up with the peonies. And so when he was in the Muppets, and doing The Muppet Show in England, he’d know that it was about time for them to bloom, so he called Kate every day. Kate was living in this house at the time.

He’d say, “Are they blooming yet?” “No, not yet.” “Okay.” So he kept calling, and finally one day she said, “All right, now they’re out, they’re coming out.” So he went right into Jim, and he said, “I gotta leave now; I gotta go see the peonies.”

And so he wanted his ashes spread on the peonies. We did that.

Many thanks to Jane Hunt, Arthur Miller, and Jessica Max Stein for this enlightening interview! For more on Jessica Max Stein and her Richard Hunt zine, visit her website.

Many thanks to Jane Hunt, Arthur Miller, and Jessica Max Stein for this enlightening interview! For more on Jessica Max Stein and her Richard Hunt zine, visit her website.

Click here to help us celebrate Richard Hunt’s life and legacy on the ToughPigs forum!

by Jessica Max Stein

I recently interviewed Richard Hunt’s mother, Jane Hunt,and her partner, Arthur Miller. We sat together in the kitchen of Richard’s childhood home, over quiche and pumpkin pie, and had a wonderful chat. Here are some excerpts. [feel free to rework opening paragraph]

JESSICA MAX STEIN: What was Richard like as a kid? It sounds like he was a born performer.

JANE HUNT: When he was about four, he’d managed to fall and knock out one or both of his front teeth, so he had a hard time talking for a while. His godmother brought him this little outfit: little corduroy pants, a little corduroy jacket, sort of like an Eisenhower jacket, and a newsboy cap, like a man on the golf range. And he came out, and he stood there leaning on his umbrella, and he said, “I’m wearing my golfing outfit.” Out of nowhere. That was adorable.

He and his brother and sisters put on performances on the landing, and they loved doing that.

When he was growing up he did all kinds of things as a Boy Scout. He took his puppets to the Boy Scouts. For many years, every year we’d have a Memorial Day picnic out in the backyard here, with people from all over [at which Richard performed].

When Richard was about 5 or 6, we were at Howdy Doody. [Richard’s sister] Kate had been chosen from the crowd of children to sit up in the peanut gallery. Richard was sitting in that audience as well, and all us parents were taken back into a little viewing studio, to watch this live show go on. It was live then, nobody had taped shows. The host, Bob Smith, was getting up and guiding them to the end of the show. Richard came down to center, tugged on Bob Smith’s coat and said, “I’m a magician, and I want to do a ‘rick.” He had no teeth in the front, from his fall. “I want to do a magic ?¢‚ǨÀúrick.'” And Bob Smith said, “Well, I don’t think we have time.” But Richard took it right out of his pocket, and he started doing the trick. I was sitting there with all these parents, like, ?¢‚ǨÀúOh my God. Oh my God.’ He’s doing this trick, something with balls, and he says — he didn’t say voila, what else do they say? Something very cute. And he completed the trick just as it went to black.

ARTHUR MILLER: He had no fear. That is very true about him.

JH: Yup, no self-consciousness about asking if he can do something or another, which I think is so great.

JMS: What were things like for Richard as a teenager? You told a story about the kids teasing Richard when he was in middle school, following him on his paper route and dropping his papers in the mud.

JH: Yeah. They tortured him. He’d never told me. I never knew anything about it until the principal told me. His office was in a corner room in the school building right across the street, which was part of Richard’s paper route, and he saw it, day after day after day. I never heard a word from Richard about it. He just shrugged it off. “They’re jerks.” He certainly didn’t let it stop him from anything.

JMS: Richard not only was a born performer, he was a born upstager.

AM: Richard had a secondary lead in a high school production of How to Succeed in Business [Without Really Trying]. The main character sings a song in the men’s room, with the chorus.

JH: [Singing] “I believe in you, I believe in you.” They’re all in front of the mirrors and they’re doing their hair, straightening their ties and stuff. All of a sudden we see Richard has pulled out of his pocket a razor, and a spray can of shaving cream. He’s singing right along. He shaved himself. He then put cologne all over himself, and the place was falling apart. The other kids were washing their hands, not knowing what the hell was going on.

AM: One gets the feeling this was not something the director had encouraged him to do.

JMS: He did that a lot.

AM: Yes, he did that a lot, and he got away with it. Most guys cannot get away with that stuff, because it’s a real no-no, it’s arrogant. Upstaging, you know?

JMS: They loved it at the Muppets. There’s some footage from the Fraggle Rock wrap party, where Karen Prell is giving a comic speech about what it’s like to be a Muppeteer, and she says, “The first rule of Muppeteering: If it moves, upstage it!”

AM: But the fact that he got away with it — almost always.

JMS: Because it’s funny!

AM: That’s a big part of it, but there’s something beyond that, I think.

JH: It’s as though everybody felt he was entitled to do whatever he wanted to do.

AM: Exactly. You give it to him. You say, “What the hell, it’s so wild to watch.”

JH: He would have spent hours with anybody in the cast, anywhere, helping them get through and do their parts and making suggestions to them. They’re not supposed to do that, but in high school I know he did.

JMS: He did it later; Kevin Clash talks about that, David Rudman talks about that.

AM: All of that stuff was in place way before he even heard of the Muppets.

JH: Yes, definitely.

AM: I can tell from these stories that — like you say, he was funny, and it was done in a generous spirit. Even though it was upstaging, there was a generosity to it.

JH: I think he would have loved it if they’d all started to shave, or something.

AM: You told me he took out Q-Tips.

JH: Oh yes. Cleaning his ears. [group laughter] Oh God, isn’t that too much.

JMS: Tell me about Richard cold-calling the Muppets.

JH: Yeah, from a pay phone. Right there on 10th and 57th. “Hello, I’m a puppeteer, can you use me?” “Well, we happen to be having a little thing going on right now. Why don’t you come on over and audition?”

JMS: That takes guts.

JH: It takes a kind of unselfconscious feeling about how you’re worth doing that. That you’re worth it.

JMS: He’s like Scooter on the Muppet Show. They couldn’t do it without him. He meets the guest star, he’s everywhere, but he’s still always this little tagalong. Scooter in the Muppet Movie, he’s the road manager because he’s the one with the van. You get the feeling that he’s a little younger, a little “Hey, wait for me.” But at the same time, he’s in. He’s part of it, he’s it! Although I don’t know how much I’m extrapolating from the plot of the show to what happened behind the scenes.

AM: Scooter was to some degree based on Richard. I think they did that with a lot of the characters, just from what I see and what I’ve heard and what Jerry [Nelson]’s talked about, that they would take the essence of the puppeteer. I think they did it unconsciously, so that there was a lot of Richard in Scooter.

JMS: Richard seemed to have a wonderful camaraderie with Jerry Nelson.

AM: Jerry was almost like a father figure. Certainly like a big brother that Richard never had. Jerry was as gifted as Richard, as soulful as Richard. I remember I once said to him, “You guys were like the Abbott and Costello for this age.”

JMS: So many of their characters. The Two-Headed Monster. Biff and Sully.

AM: They ad-libbed their asses off on that show.

JH: They really intuited all that stuff.

JMS: Another great one is Placido Flamingo.

JH: “Oh, Ree-chard!” One day I was walking home, past the Met, and going into the Met was Placido Domingo. I thought, “Richard would do this,” and I just walked right up, and I said, “Mr. Domingo, I’m sorry to bother you, but I wanted you to know that I’m Richard Hunt’s mother.” And he said, “Oh, Ree-chard! Hello! I am so sorry.”

JMS: One thing I like about what I’ve learned about Richard is his sense of abundance. It’s really easy to think that things are scarce, that love is scarce, money is scarce, and the stories that I see about Richard show that he really lived with abundance.

JH: That’s a very good word.

AM: Everyone tells these stories about Richard’s, what I call pathological generosity, almost crazy generosity. Once he hit it big, he wasn’t married, he didn’t have any children, he was never big with clothes and stuff, he just bestowed it.

He would take the family on these big junkets, these Hunt junkets. He took us all to Hawaii. The Hunt family was not just the brothers and sisters. There was a second ring of people who are as good as brothers and sisters. So he took between 15 and 20 of us to Maui, for a week, at one of the fancy-schmanciest, goyishe places. All white belt, white shoes, and into this milieu comes the Hunts, who change into their bathing suits in the parking lot, you know.

I would watch Richard working the planes when we would travel. He’d find any kids on the plane and he would approach them. Of course, at first the parents would have no idea who he was, he wouldn’t be working a Muppet or anything. And I would watch. You know the way people first are, “Who is this?” And then they do that turn, that shift, without even realizing it, they’re drawn right in. And then they’re watching their child dig Richard.

One of the things I always heard him say that would knock people out, to a little kid, is he would look at him and say, “You’re sick.” The kid would laugh at some joke or say something that a kid would say, some disgusting little thing, and Richard would look at him and say, “You’re sick.” And the kid would just love it.

I think he must have given something to more people than you could possibly imagine. Especially kids, who are so used to being condescended to or dismissed or pushed around or “Say thank you to the nice man,” all that stuff, and he would have none of that.

JMS: When did Richard come out to the family?

JH: Well, the first thing I knew anything about it was after that thing that you described of the time when [Kate and Richard] went waterplaning and crashed on the parkway, when Richard told Kate [that he was HIV-positive, around 1987]. She didn’t come running around telling everybody.

AM: He never really came out.

JH: No, he didn’t really come out.

AM: It was obvious, it was made clear, but he didn’t announce it.

JH: He kept things very separated, and in their places, where they belonged. Once he brought a group of guys to my house one night, I knew all these guys were gay. Did I know that Richard was at the time? I’m not really sure.

AM: I have a feeling there was a period in your family when everybody sort of knew. He would start to show up with guys, right?

JH: Yup.

AM: And nobody really said anything, you used to say to me.

JH: No, no. We welcomed them all the same, whoever it was, come on in. There was one boy who used to come over — he must have gotten out early from school, or he cut class or something, and he would come over here, and he’d sit on the floor with his back against the couch, and just wait for Richard to come home. And sometimes Richard wouldn’t come home, and so he would get up and say, “Well, I’m gonna go now.” That was all that was ever said.

JMS: You tell a story of a lover who predeceased him, who died in his arms. Do you remember who he was?

AM: The guy that Richard was with at the end, I forget his name, and I’m embarrassed. They lived together. And when he died — this was a guy who sat in a room, he was gorgeous, but he barely spoke. Richard threw a memorial for this guy, it predated the Henson memorial, in St. John the Divine.

JH: In one of those off to the side chapels.

AM: He threw this memorial with a gospel choir, and a string quartet. This guy was very quiet. Most of them were very quiet, sat quietly. Richard ran the show. Richard drew everybody around, and most of the guys he was with, from the time I knew him, were quiet, not overt. The last one hardly spoke at all. I never really saw him with a guy who was — like Richard, for example. Expansive.

JH: Richard was so unabashed, everybody knew, that I think lots of his partners weren’t used to the kind of openness they found in our family and in our family’s crowd. Certainly the guys in the Muppets, the guys at Sesame Street, were not in any way concerned about any of this.

JMS: I love the story that you tell about Frank Oz being at his bedside in his dying days. People ask me if he was out at the Muppets, if they were okay with it, and I just say, “Frank Oz was at his bedside when he was dying, and if that doesn’t tell you that they were okay with it, nothing will.”

JMS: I was curious about what Richard was like spiritually. I know he grew up going to the Episcopal Church.

JH: Yeah.

JMS: And then I know that Richard and David Rudman went to Macchu Picchu, and Rudman says that was like a spiritual pilgrimage. I know it’s a fine line. Maybe his art and his work and his life, living in the moment and all that, that is a kind of spirituality, but I was curious if he was ever more explicit about it.

JH: No, not in the sense of going to church every Sunday or anything of that nature. But I think he was spiritual. We’re the kinds of people who would be driving along in the car and say, “Look at that!” That kind of thing, that’s what we were all about. Everything new. When we were on Maui it was simply gorgeous. We appreciated every single bit of it. The whole family is like that.

AM: You know, I was just thinking, we were talking about Richard coming out. I think that was his spirituality. I think he kept that sort of to himself.

JH: Very private.

AM: You’d have to extrapolate it.

JH: I think many of these little deeds I love to talk about [exemplify his spirituality]. He was on Central Park West, and there were two old ladies with suitcases out on the curb, waiting, trying to get a cab and the cabs wouldn’t stop. So he had to walk over and say to them, “What is happening here?” “We need to get to the airport and the cabs won’t stop.” So up went Richard’s hand, he stopped a cab, said “Get in,” opened the door for them, got them in, “Tell them where you’re going,” and in the meantime he put the bags in the trunk of the car, gave the guy probably forty dollars or something, and sent them on their way. Now to me that’s spiritual.

The woman who was crying her eyes out because she wanted to kill herself, down there by the pond in Demarest. He noticed this woman crying, in the car, when he drove by. He stopped his car, got out, went back and said, “What’s the matter?” “I want to die, I want to die.” He said, “Just a moment,” and with that he hailed another car, said, “Please call the police right now, we need this woman to be taken care of,” and he stayed there with her and talked with her until the police came and took her off to the hospital. I think he thought, “That’s what I’m here for.”

This is a story you’ll love. There was a hurricane coming, up on Cape Cod. Everybody was asked to leave their cottages and go to the high school.

AM: Higher ground, to get away from the water. The cottages, the dunes, were right on the water.

JH: Richard had not been feeling well. Our friends Mary and Sonny were up there. They were seeing to it that he was fed and his sheets were clean and stuff like that. This is just before he died. I don’t think he even went back to the Cape after that time.

Anyway, Richard did not want to evacuate. He said to Mary and Sonny, “Go on. You just go ahead and go about your business. I’ll be fine.” Well, didn’t he go and climb out his bedroom window, and sit on the porch roof, looking out over Cape Cod Bay, with the pilgrim monument down there in P-Town, and he sat up there during that storm hugging his knees, watching the storm come in.

There’s the spirituality for you. To be sure.

JMS: Richard died on January 7, 1992, in the Cabrini hospice in Manhattan. What was his memorial like?

JH: Richard had a funeral at St. John the Divine. It was just unbelievable. There were just as many people at his who were at Jim Henson’s. The place was jammed. It was amazing. Fred Newman got up and told the story of the time that he and Richard went to the Plaza for lunch. Fred said, “I had it in my head all along that he was not going to pay.” So he called for the check, and the guy puts it down, and he reaches to grab it, and Richard grabs him back. They’re struggling, fighting over this check. They absolutely got out of their chairs, and were on the floor! The maitre d’ came over and said, “Gentlemen, is there a problem?” That just brought the house down at St. John the Divine.

[The family home in New Jersey] is where the peonies bloomed every year. He grew up with the peonies. And so when he was in the Muppets, and doing The Muppet Show in England, he’d know that it was about time for them to bloom, so he called Kate every day. Kate was living in this house at the time.

He’d say, “Are they blooming yet?” “No, not yet.” “Okay.” So he kept calling, and finally one day she said, “All right, now they’re out, they’re coming out.” So he went right into Jim, and he said, “I gotta leave now; I gotta go see the peonies.”

And so he wanted his ashes spread on the peonies. We did that.